It’s now official: the South China Sea does not belong to China. Official, that is, according to a new ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Not so official, however, for China itself, which has summarily rejected the ruling, saying it “will neither acknowledge it nor accept it.”

The court ruled that China has no standing to claim the vast area within the famous “nine-dash line,” encompassing roughly 90 percent of the South China Sea and thus all the resources that may exist within it.

The court’s decision, announced on July 12, was widely anticipated and, in some quarters, eagerly awaited. The case had been brought in 2013 by the Philippines after China refused arbitration regarding its territorial claims.

While the South China Sea has been a source of territorial dispute for many years, involving all of its bounding nations, China has been particularly aggressive of late, building artificial islands, installing military facilities, drilling for oil and gas, and chasing off the boats of its Southeast Asian neighbors from waters UNCLOS says they can operate in. With the Philippines, it has been especially belligerent over the Scarborough Shoal, a fishing ground roughly 125 nautical miles from Luzon and 1,435 nautical miles from China.

China’s claims also reach well within the 200-nautical-mile limit of several other nations’ EEZ. In the case of Malaysia and Brunei, the nine-dash line even reaches operating oil and gas fields, suggesting that China might one day think about seizing them for its own use.

Or so some China watchers believe. Assumptions of a similar kind have often led observers to state that Chinese interests in that sea are largely resource-based. This means oil and gas resources, above all, with smaller attention to fishing.

But how much oil and gas is actually in the South China Sea? Is that what this is really all about? What’s actually at stake for China and its neighbors?

My years as a geoscientist in the energy industry and close observation of the region’s geopolitics lead me to believe it’s about a lot more than a few billion barrels of oil.

What’s down there

Statements about how much petroleum there might be have ranged wildly, from a few hundred million barrels of oil to hundreds of billions (on the scale of what’s in the Persian Gulf).

Are there any dependable estimates?

To date, the best evaluations in the public domain are those by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the Energy Information Administration (EIA) of the U.S. Department of Energy. More detail is offered by the 2012 USGS report, whose figures allow one to assess volumes of undiscovered oil and gas might within the nine-dash line area.

USGS geoscientists divide the region into distinct petroleum basins and platforms whose extent can be compared with China’s territorial claims. My own rough estimate based on this data is that a mean of around 3-3.5 billion billion barrels of oil and 65-70 trillion cubic feet (1.4-2 trillion cubic meters) of natural gas, are down there. That suggests there’s more gas up for grabs than oil, and it’s confined largely to the Sunda Shelf and Dangerous Ground area (Spratly Islands and environs).

In truth, however, much of the geology in this region remains only poorly understood, and any resource estimates must still be considered preliminary.

All about oil?

Such volumes, if even partly accurate, are definitely meaningful for a nation like the Philippines or Malaysia, but not so much for China.

As the world’s largest importer of crude, China brings to its shores and borders around 7.5 million barrels a day, or 2.7 billion barrels a year. It faces a future of long-term, growing dependence on major exporters, many of whom are far away and have many tens of billions of barrels in reserves. This, then, provides a clue.

Oil is the one energy source the world, including China, cannot do without. It powers more than 90 percent of global transportation, which makes it absolutely essential to every modern economy and every military.

Oil, moreover, is the one source with no alternatives on a mass scale. The world is working on some (biofuels, electricity), but it will be several or more decades before they can replace this energy-rich, flexible, easily transported fuel source, with its multi-trillion-dollar global system of supply and use.

China understands this all too well, not least its military, which appears to be in charge of building the artificial islands in the Spratlys and installing airstrips, radar and more, as well as new weapons systems in the Paracel Islands to the northwest.

Fully 66 percent of China’s oil imports, which are now over half of all consumption, come from the Persian Gulf and Africa and so move through the South China Sea. To say this another way, 82 percent of the country’s maritime imports come by this route.

It does not take an unbounded imagination to comprehend the security dilemma this might present to a rising world power. A power, moreover, whose chief and far more formidable rival has control of the neighboring ocean (the Pacific, in this case), strong alliances with surrounding nations (India, Vietnam, Philippines, Korea, Japan) and a major trade initiative underway (Trans-Pacific Partnership) that, from one perspective, would bring other nations of the region further into its influence.

Or about an idea?

There is another point to make. China’s main claim on the South China Sea is based on history, or rather, a certain nationalistic view of history.

In a 2000 document, “Evidence to Support China’s Sovereignty over Nansha [Spratly] Islands,” China’s Ministry of Foreign affairs states that “China was the first to discover, name, develop, conduct economic activities on and exercise jurisdiction of the Nansha Islands.”

To Western eyes, this claim reads like something out of a 19th-century territorial grab. Going back to the East Han Dynasty (A.D. 23-220), it traces a path through ancient and medieval texts before emerging in official bodies (e.g., the Chinese Toponymy Committee) of the modern era. There is a distinct aroma of national destiny: explorers, soldiers, fishermen, “the Chinese people” (often repeated) made the region “an inalienable part of Chinese territory.”

In all likelihood, it would be a mistake to write this kind of sensibility off as pure fabrication, a crude attempt to rationalize expansionary actions. We in the West have often seen the potent and deforming forces of nationalism at work in the past century, after all. Indeed, we are seeing them in action today, both in Europe and the U.S., in disturbing forms that curl inward rather than outward.

In this sense, the South China Sea is not only a territory to claim for security reasons. It is also an idea. This is not the idea of “China’s Monroe Doctrine,” as often advanced. It is something unique to the present, a complex mixture of nationalist fervor, insecurity, ambition and identity-making.

What comes next

China, in fact, has risked a good deal by its moves in the South China Sea.

The ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration is blunt and far-reaching. It says China has violated its neighbors’ sovereign rights, specifically the Philippines, turning atolls into artificial islands, chasing away Philippine vessels from an area within their own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and allowing Chinese fishermen to harvest what they like, including endangered species like sea turtles and giant clams. In so doing, China has caused “severe harm to the coral reef environment,” thereby abjuring “its obligation to preserve and protect fragile ecosystems.”

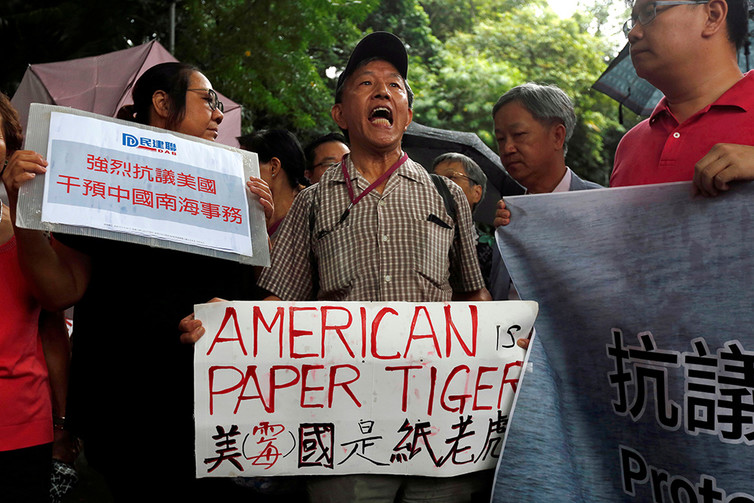

Beijing, predictably, rejects not only the court’s ruling but even its authority. Yet the determinations are clearly serious and will affect, in less than favorable ways, China’s international prestige, something the country does not take lightly. China will continue its development in the sea and will seek, as it has done in the past, to deal with its neighbors on a bilateral basis.

Viewing this evolving situation as a matter of resource anxiety or military expansionism (or both), however, won’t do it justice. This shouldn’t be taken to mean that the U.S. or South China Sea nations should go softly or back down from confronting China, especially when it acts aggressively. Not at all.

But it helps us to understand what is at stake, as China continues to carve a greater place of sovereignty and identity in a world dominated by an increasingly troubled West.

![]() Scott L. Montgomery, Lecturer, Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington

Scott L. Montgomery, Lecturer, Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.