A federal appeals court on March 26, 2025, upheld a temporary block on President Donald Trump’s deportation of hundreds of Venezuelan immigrants, including alleged members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua, to a maximum security prison in El Salvador.

The court was skeptical of Trump’s use of the Alien Enemies Act to defend the deportations. The act, passed in 1798, gives the president the power to detain and remove people from the United States in times of war.

On March 28, Trump asked the Supreme Court for permission under the act to resume deporting Venezuelans to El Salvador while legal battles continue.

Attorney General Pam Bondi previously said the deportations are necessary as part of “modern-day warfare” against narco-terrorists.

Nanya Gupta, policy director of the American Immigration Council, is among experts who note that the Trump administration’s evidence against the migrants, which relied in part on the immigrants’ tattoos and deleted social media pictures, is “flimsy.”

Those who are challenging Trump’s actions in court say the administration has violated constitutional principles of due process. That’s because it gave the migrants no opportunity to refute the government’s claims that they were gang members.

But what is due process? And how does the government balance this important right against national security?

As a constitutional law professor who studies government institutions, I recognize the delicate balance government must strike in protecting civil rights and liberties while allowing presidential administrations to preserve national security and foreign policy interests.

Ultimately, the U.S. Constitution’s framers left it to the courts to determine this balance.

Due process explained

The phrase “due process of law” goes back to at least 1215. That’s when England’s Magna Carta established the principle that government is not above the law.

This principle guided the framers of the U.S. Constitution. The Fifth Amendment and 14th Amendment, for example, prohibit federal and state governments from depriving people of their “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

But what constitutes due process has varied over time.

Government officials see the limits of their power from one lens. People affected by the exercise of that power view it differently.

To combat this problem, the Constitution’s framers placed the judiciary in charge of determining what due process means and when people’s due process rights have been violated.

Court decisions on the issue traditionally weigh the government’s interests in taking specific actions against claims that those actions violate people’s civil rights and liberties.

Even when the law authorizes the president to detain people, historically the Supreme Court has held that those people should receive notice of the reason for their detention, and they should have a fair opportunity to rebut the government’s claims.

When the high court, for example, heard cases about the rights of detainees held in Guantanamo Bay by President George W. Bush after 9/11, it ruled that principles of due process apply to noncitizens and even those whom the government designates as enemy combatants.

One of the important considerations in legal analysis of the procedures the government must follow when depriving people of their liberty is the risk that the government will make a mistake in its decision-making.

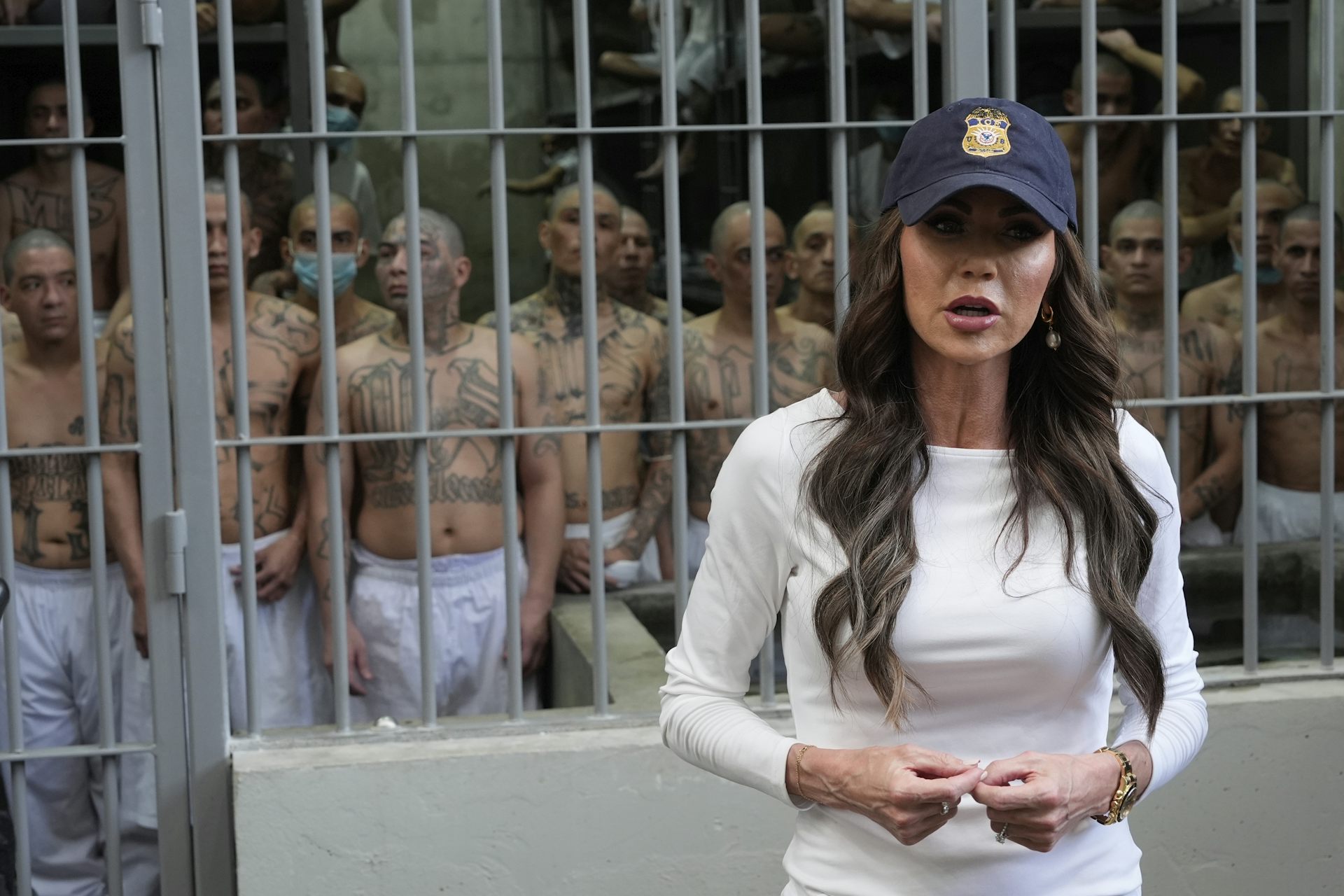

For example, some representatives of the deported Venezuelan migrants argue that they have been falsely accused of having ties to Tren de Aragua based on their country of origin and tattoos. They claim that without more investigation, including an opportunity for the migrants to present their evidence refuting the government’s claims, there is a large risk that government will mistakenly deport people.

When can the president avoid due process?

In some cases, the president can skirt traditional due process considerations in pursuit of broader policy concerns.

As put by U.S. District Judge James Boasberg in his initial order blocking the deportations, the president’s action in this area implicate “a host of complicated legal issues, including fundamental and sensitive questions about the often-circumscribed extent of judicial power in matters of foreign policy and national security.”

Before Trump took executive action using the Alien Enemies Act, the measure had only been used three times – all during times of war.

The act was part of a series of four laws passed in 1798 known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws, among other things, gave the president the power to deport any noncitizen thought to be dangerous.

President Thomas Jefferson allowed most of the acts to expire. But Jefferson and subsequent presidents kept in place the provisions that empowered the president to detain or deport noncitizens in times of war, “invasion” or “predatory incursion” by foreign powers.

Today, the law authorizes the president to apprehend and remove people over the age of 14 that the administration determines to be “alien enemies.” However, it places procedural requirements on the president.

Notably, the president’s ability to act requires a declared war against or an “invasion or predatory excursion” by a foreign nation. In such an event, the president must issue a proclamation saying he plans on using the act against perceived enemies.

To justify the Venezuelan deportations, Trump issued a proclamation on March 15 claiming Tren de Aragua is perpetrating and threatening an invasion against the U.S.

But the act also says people considered alien enemies must be given reasonable time to settle their affairs and voluntarily depart from the country. And it gives the courts power to regulate whether such persons even fall within the definition of “alien enemies.”

The Venezuelan migrants claim Trump has violated these parts of the act.

The current fight

This is where things become complicated.

All parties in the case acknowledge that the Alien Enemies Act grants the president authority to act. However, the argument is whether the government has given people the opportunity to challenge the government’s decision to classify them as “alien enemies.”

Trump claims Tren de Aragua is a foreign terrorist organization engaged in warfare against the U.S. in the form of narco-terrorism – the use of drug trade to influence government operations.

His administration argues that it doesn’t have to tell migrants it considers them alien enemies. And the administration says it’s not required to give them time to ask the courts to step in before they are deported.

In a March 24 hearing on the issue, D.C. Circuit Court Judge Patricia A. Millet noted that during World War II, even the “Nazis got better treatment under the Alien Enemies Act.”

The dispute has prompted international questions about the legality of the U.S. government’s deportation procedures and its treatment of the migrants.

And Democratic members of Congress have called for an investigation into the administration’s deportation practices.

The case will most likely head to the Supreme Court to determine what due process means and when the president can act in the name of national security to limit people’s due process rights. That’s just as the framers of the Constitution intended.![]()

Jennifer Selin, Associate Professor of Law, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.