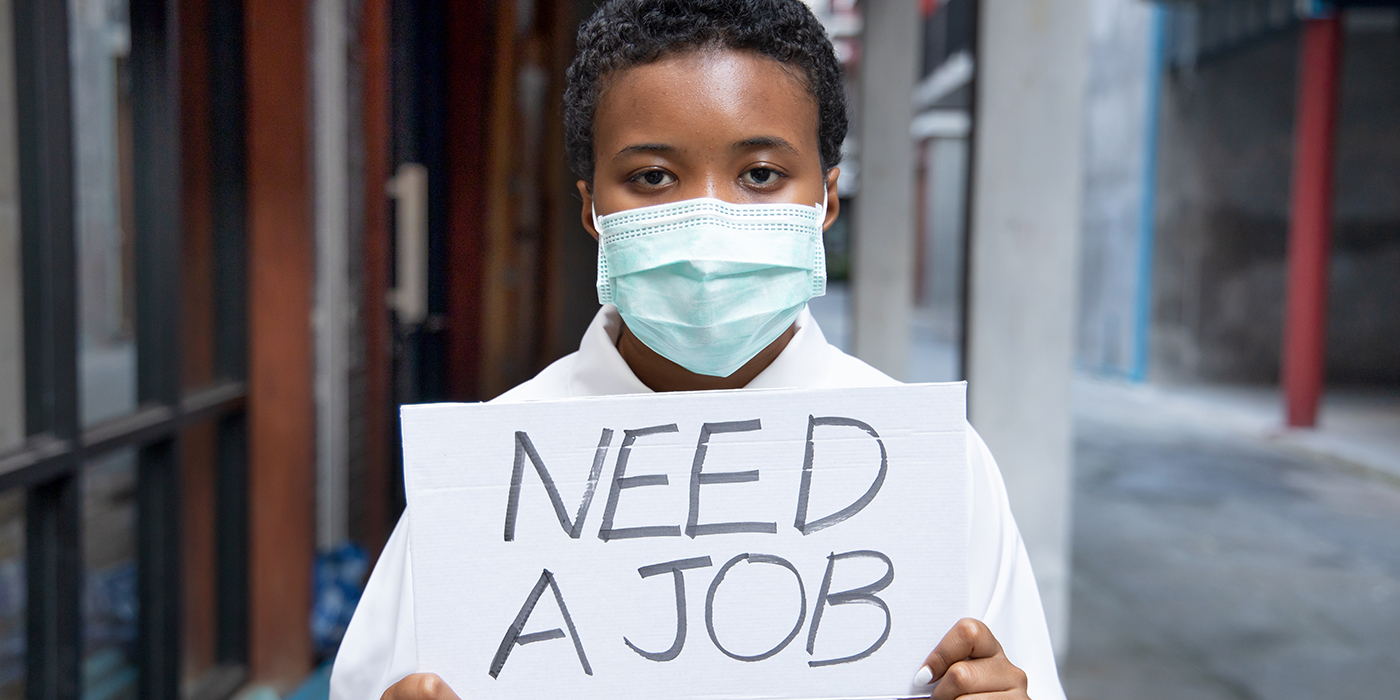

Unemployment fell to 6% in March, according to an April 2 U.S. Department of Labor report. The strongest gains were in leisure and hospitality and construction. The news was better than expected, but aggregated data doesn’t always tell the full story according to economists at Washington University in St. Louis. The unemployment rate in March for white Americans was 5.4% while it was 9.6% for Black Americans.

Generally speaking, recessions disproportionately hurt economically disadvantaged groups. The current recession created by the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. It has especially impacted women — particularly Black and Hispanic women — and less educated workers, magnifying existing U.S. employment inequality, according to new research conducted by Steven Fazzari, Professor of Economics in Arts & Sciences, and senior Ella Needler, an economics major and a student in the Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis.

And the effects of this inequality will likely be felt long after the recession both in terms of employment and economic growth.

“Unemployment creates economic hardship and psychological stress for individuals and families,” said Fazzari, who also directs the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government and Public Policy at Washington University. “Of course, unemployment wastes valuable productive resources. But inequalities in the way recessions destroy jobs magnify the personal and social costs.”

Fazzari and Needler developed a novel tool to measure inequality — what they label “job-months lost” — that captures both how much employment declines during a recession and the persistence of those declines to compare the inequality in U.S. employment across social groups during the Great Recession and the year-plus-long COVID-19 pandemic.

“There’s a tendency to consult aggregated data when interpreting the state of the economy,” Needler said. “But aggregated data can hide disproportionate effects that impact important groups.”

Their research exposes the unequal ways in which the recession has impacted women, lower income and minority workers. It also makes the case that policies designed to stimulate the economy should provide disproportionate relief for those most hurt by the pandemic.

Comparing job losses during the Great Recession and COVID-19

The research showed a significant shift of job losses from men in the Great Recession to women in the current economic crisis induced by the pandemic. The 2008-09 recession hit manufacturing and residential construction employment particularly hard, both sectors in which men constitute a much larger share of employment than women. In contrast, COVID-19 hit service jobs particularly hard in industries such as restaurants, travel and health care — all sectors in which women hold a larger share of the jobs. Women have also been disproportionately affected by additional childcare duties as COVID-19 shut down schools and childcare centers.

In both recessions, white workers fare better than Asian, Black and Hispanic employees. However, the COVID-19 pandemic — in their words — “decimated” Black and Hispanic women’s employment with their share of job-months lost 42% and 60% higher, respectively, than would be expected given the share of these groups in the February 2020 employment. Asian women had severe job-months lost in the COVID-19 months, but they also suffered inequality in the Great Recession.

The research also showed young workers suffered disproportionate, and similar, job losses in both recessions. Middle-age workers have been affected less severely in the COVID-19 crisis than in the Great Recession, while older workers have done much worse during COVID-19 compared with their experience amid the Great Recession.

Less educated workers have suffered dramatically more employment loss due to COVID-19 than more educated groups: For workers with less than a high school education, job-months lost were nearly double their share in pre-pandemic employment; losses for college graduates were half as large as their employment share. Inequality across education groups in the Great Recession was far less pronounced.

“Less educated workers are more concentrated in sectors such as restaurants, hospitality and retail that have been decimated by the public health crisis,” Fazzari said. “These jobs also cannot be done remotely. In contrast, college-educated workers are much more likely to be able to work from home. When more educated and relatively affluent people stop going out to restaurants and stop shopping to protect their health, it is the less educated, lower-income people who lose their jobs.”

Long-term impact of unemployment

Even with the job gains in March, Needler points out total employment “is still 8.4 million jobs below what is was in February 2020 and 55 percent of these remaining losses are women.” Permanent job losses and detachment from the labor force during the COVID-19 crisis will likely have widespread effects on employment prospects for years to come, and these effects will be greater for disadvantaged groups, she emphasized.

“For all workers, unemployment and time out of the labor force compromises future employment and wage prospects,” Fazzari said. “Perhaps the unusual circumstances of the COVID-19 crisis will mitigate the stigma of unemployment for job searchers, but longer-term negative consequences are likely. And, because of the great inequality in COVID-19 job losses, any unemployment stigma will be highly unequal.”

Impact of inequality on economy

Shifting focus to the broader economy, the rising inequality created by the COVID-19 pandemic has decreased consumption and demand. The primary reason is simple: high income groups recycle less of their income back into consumption than those with moderate or low incomes, Fazzari said.

If the unequal employment effects drag on, it has the potential to slow economic growth.

“The connection between recessions, inequality and macroeconomic policy has another, somewhat more subtle, implication,” the authors write. “Our results demonstrate how individuals and families in lower socio-economic circumstances suffer more severe effects from the recession. The goal of social equity, therefore, implies they should receive disproportionate relief from policies designed to stimulate the aggregate economy.