Gadsden flags fly at a protest Wednesday at the Capitol. Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

Flown by many protesters at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, the Gadsden flag has a design that is simple and graphic: a coiled rattlesnake on a yellow field with the text “Don’t Tread On Me.” But that simple design hides some important complexities, both historically and today, as it appears in rallies demanding President Donald Trump be allowed to remain in office.

The flag originated well before the American Revolution, and in recent years it has been used by the tea party movement and, at times, members of the militia movement. But it has also been used to represent the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. men’s national soccer team and a Major League Soccer franchise.

As a scholar of graphic design, I find flags interesting as symbols as they take on deeper meanings for those who display them. Often, people use a flag not because of what is explicitly displayed, but because of what the person believes it represents – though that meaning can change through time, and with one’s perspective, as has happened with the Gadsden flag.

The beginning of a myth

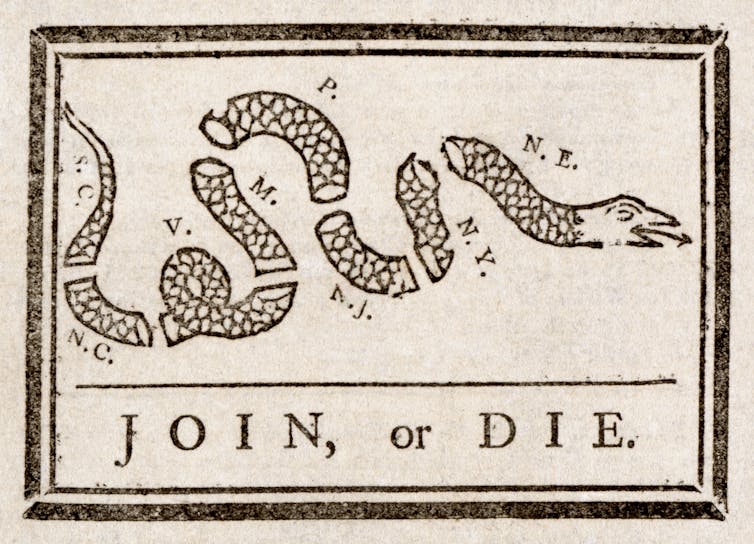

The flag’s origin isn’t entirely clear. It seems to begin with a simple illustration accompanying an essay by Benjamin Franklin in 1754, 20 years before American independence. The image, possibly drawn by Franklin himself, portrays the American Colonies as parts of a divided snake, simply stating “Join, or Die.” The essay it accompanied addressed the major current issue for British colonists in North America: the threat of the French and their Native American allies.

Later, as the American Revolution took shape, the image took on a new meaning. Colonists hoisted various flags, including ones depicting rattlesnakes, a distinctly American creature believed to strike only in self-defense. The flag commonly known as the “First Navy Jack” had 13 red and white stripes, and possibly a timber rattlesnake with 13 rattles, above the words “Don’t Tread On Me.”

In 1775, as the American Revolution began, South Carolina politician Christopher Gadsden expanded on Franklin’s idea, and possibly the red-and-white flag as well, when he created the yellow flag with a coiled rattler and the same phrase: “Don’t Tread On Me.”

Gadsden was a slave owner and trader, who built Gadsden’s Wharf in Charleston, South Carolina, which was a major slave-trading site. As many as 40% of enslaved Africans who were brought to the U.S. first arrived there. The site is slated to be the home of the International African American Museum, which estimates that 150,000 captured Africans came through the wharf, and that between 60% and 80% of today’s African Americans can trace an ancestor to the trade there.

A symbol awoken

For most of U.S. history, this flag was all but forgotten, though it had some cachet in libertarian circles.

The First Navy Jack version resurfaced in 1976 on U.S. Navy ships to celebrate the nation’s bicentennial, and again after 9/11, though today that flag is reserved for the longest active-status warship. Its use remained largely apolitical.

In 2006 the slogan and the coiled snake saw some commercial use by Nike and the Philadelphia Union, a Major League Soccer team.

Around the same time, though, the flag took on a new political meaning: The tea party, a hard-line Republican anti-tax movement, began using it. The implication was that the U.S. government had become the oppressor threatening the liberties of its own citizens.

Perhaps as a result of the tea party movement, several state governments around the country offer a Gadsden flag license plate design. At least some of those plates charge additional fees for the special plate, sending proceeds to nonprofit organizations.

The Gadsden flag has appeared at other political protests, too, such as those opposing restrictions on gun ownership and objecting to rules imposed in 2020 to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Most recently the flag has been flown and displayed at some post-election protests, including events where demonstrators called for officials to stop counting votes – and both inside and outside the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., during the counting of the electoral votes on Jan. 6.

Because of its creator’s history and because it is commonly flown alongside “Trump 2020” flags, the Confederate battle flag and other white-supremacist flags, some may now see the Gadsden flag as a symbol of intolerance and hate – or even racism. If so, its original meaning is then forever lost, but one theme remains.

At its core, the flag is a simple warning – but to whom, and from whom, has clearly changed. Gone is the original intent to unite the states to fight an outside oppressor. Instead, for those who fly it today, the government is the oppressor.

Editor’s note: This article was updated Jan. 7, 2021, to include additional information about Christopher Gadsden, the flag’s original designer.

Paul Bruski, Associate Professor of Graphic Design, Iowa State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.