On Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2001, I anticipated a busy but relatively calm day at the White House.

I was the special assistant to the president for management and administration, and President George W. Bush was in Sarasota, Florida, promoting the No Child Left Behind legislation. The senior official in the White House was Vice President Dick Cheney. First lady Laura Bush was scheduled to travel to Capitol Hill to brief senators on early childhood education. On the South Lawn, tables were being set up for that evening’s congressional barbecue.

With the president away, I arrived later than usual that morning and headed to a breakfast in the small senior staff dining room known as the White House Mess, on the ground floor of the West Wing.

I was sitting at a table eating my toast and drinking coffee when a colleague came over and told us about news reports of a plane crashing into the World Trade Center in New York City. We thought it had to be a terrible accident. We left the Mess shortly thereafter, unaware of the impact of the second plane.

‘Get out now’

This story began as an assignment from the White House Historical Association to write about that day for its 9/11 20th-anniversary edition of the White House History Quarterly. I interviewed a range of White House staffers, from Cabinet officials and aides assisting the vice president and the National Security Council to the interns from around the country who had begun their service at the White House that momentous day.

In the minutes after we heard about the plane crashing, there was a rush of activity in the ground-floor hallway. I was directed by the Secret Service to get West Wing staff out of their offices and into the windowless Mess, which was thought to be the safest place at the time.

But then, the agents, weapons drawn, ordered everyone to “get out now,” sending staffers racing through the iron gates that had been opened at both ends of West Executive Avenue outside the West Wing. Women were advised to kick off their heels and run for their lives. Tourists at the White House ran from the building, leaving strollers on the lawn.

Across the White House complex, the Secret Service ordered staff to evacuate as quickly as possible. In the five-story Old Executive Office Building next door, however, many staffers learned about these orders only by watching TV and seeing the chyron: “White House being evacuated.”

The frantic evacuation was a response to the urgent call the Secret Service had received from air traffic control at Ronald Reagan National Airport – in which Secret Service staffers were told, “There is an aircraft coming at you” and “What I am telling you, buddy, is that if you’ve got people, you better get them out of there. And I mean right goddamned now.”

Moments later, hijackers crashed American Airlines Flight 77 into the Pentagon. The vice president had been evacuated from his West Wing office to the president’s emergency operations center, also called “The Bunker.” An agent later said, “We had 56 seconds to move him.”

The ‘Dead List’

In the White House Situation Room, which served as the vital link for secure communications and information for the president, staff were told by their senior duty officer that “we have been ordered to evacuate … If you want to go, go now.”

But no one moved.

The communications technician transmitted the list of personnel who remained to the CIA Operations Center. The duty officers there called it the “Dead List.” Thankfully, their description was ultimately wrong.

I left the White House and joined staffers across the street in Lafayette Park. I instinctively sought to find a safer place to congregate and thought of the DaimlerChrysler office on H Street, a short walk away. My husband, Tim McBride, a former aide to President George H.W. Bush, was serving as director of government affairs for DaimlerChrysler in its Washington office.

I called Tim and asked if I could bring White House staff members there. Tim had already begun to send his staff home, and thought quickly to ask them to leave their computers on with their passwords written down, so that White House staffers would be able to work in the office.

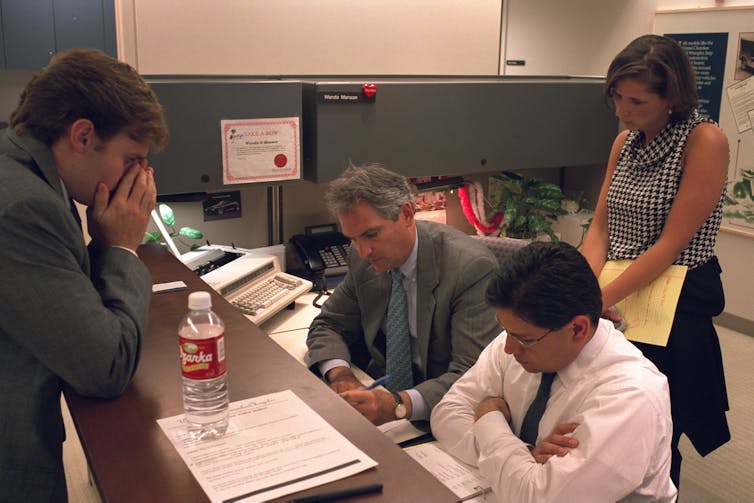

Ultimately, more than 70 White House personnel from offices including speechwriting, scheduling, communications, Oval Office operations and legislative affairs worked from DaimlerChrysler on 9/11. I asked one of the first staff members to arrive to sit at the front desk and record everyone’s name and contact number and fax that list to the White House Situation Room, notifying them who was at this location.

‘Bond deepened’

Speechwriters began researching for presidential remarks, communications staff were monitoring reports from around the country and keeping contact with the media, and senior staff took charge, giving directions to create a schedule of events for the president’s next few days, including going to New York and the Pentagon.

In horror and grief, we watched the news of the hijacked plane that went down in a field in Pennsylvania, but the mood in the DaimlerChrysler office was focused and determined. As one colleague said, “the culture of the White House stuck with people in the face of an emergency.”

Word reached us around 5 p.m. that West Wing staff should head back to the White House. The president was returning. Going room by room at the DaimlerChrysler office, I collected any documents that were left behind. These materials were now presidential records to be preserved at the National Archives.

Making my way back to the White House to get my car, I walked through Lafayette Park. The country was now at war, and everyone knew it was the start of a new chapter in our nation’s history. As one former colleague told me, “Working at the White House is a binding experience in itself, but the strengthening of that bond deepened after an experience like this.”

Anita McBride, Fellow in Residence, Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies, Department of Government, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.