In its hearing on Oct. 13, 2021, the Supreme Court appeared to favor reinstating the death sentence for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was found guilty of planting homemade bombs, with the help of his brother, Tamerlan, along the crowded Boston Marathon route on April 15, 2013. The bombs killed three people and injured 260.

As the brothers evaded police, they killed a police officer and injured many others. In attempting to escape, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev accidentally killed his brother by running him over with a vehicle.

Prosecutors brought the case to the Supreme Court after the First Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the death sentence for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on the grounds that the prospective jurors were not screened sufficiently about their exposure to media coverage of the bombing, and the jurors were not given evidence of Tamerlan’s past crimes.

Tsarnaev’s lawyers wanted jurors to consider the influence of his older brother as a mitigating factor to lessen his sentences, and the evidence of Tamerlan’s past violence was a key part of that argument.

I study criminal law and punishment as a political institution, including how it must fit within the values of a liberal democracy to be justified. Tsarnaev’s case is complicated because of the immense harm he caused to so many people.

My research examines how punishment affects members of society beyond the criminals and their victims. One of the key ways that punishment has a broader social effect is its capacity to express strong moral condemnation of actions that violate the basic rights of members of society.

But punishment also expresses moral condemnation of the criminal. This is where the risk comes in because a strong negative attitude toward one individual can reinforce prejudicial stereotypes about racial and ethnic groups.

Punishment and collective condemnation

Joel Feinberg, one of the most influential philosophers of law in the 20th century, explained that punishment has an “expressive function.” By this, Feinberg meant that punishment expresses the idea that the government condemns the criminal action. Criminal conviction is not enough to express moral condemnation on its own, because punishment is necessary to show that criminal laws are more than empty words.

The capacity of punishment to send a message makes it useful for reinforcing a society’s values. In liberal democracies like the United States, the government represents members of society. Thus, punishment is one way that society expresses its values. Not only does the fact of punishment communicate that the society condemns an action, but also the severity of the sentence communicates how much it condemns the criminal act.

Feminist political theorist Jean Hampton explained that the expressive capacity of punishment is valuable because it allows society to convey solidarity with the victims of crime. When people commit crimes, Hampton argued, they put their own goals and interests above those of the people they harm in the process. In cases of violent crime, this is especially true. Punishing Tsarnaev is a way of communicating that society values the lives of the victims.

If the idea that punishment communicates solidarity with victims seems abstract, consider a case where a crime was inadequately punished. Brock Turner, a Stanford student who was found guilty of sexual assault of an unconscious female student, was sentenced to just six months in county jail, though he would only serve half that. Many people were outraged at the short sentence, given the nature of his crime and the strong evidence against him.

Stanford law professor Michele Dauber led a successful campaign to recall the sentencing judge, and when she won, she said, “”We voted that sexual violence, including campus sexual violence, must be taken seriously by our elected officials and by the justice system.”

The sentence was interpreted as a lack of solidarity with the victim and with all victims of sexual assault. The recall was a message to other judges that citizens wanted harsher punishments for rapists because harsher sentences would convey that the lives of victims of rape matter.

The capacity of punishment to communicate a society’s values is useful, but it can also reinforce negative attitudes toward the person who committed the crime – not just toward the criminal act itself.

In the Tsarnaev case, victims and strangers alike have moral reasons not only to condemn his criminal actions but also to condemn him. It would be understandable if people resented him or held other negative attitudes toward him, given the nature of his crime. When he is punished, the state is reinforcing and justifying those attitudes as legitimate.

Risks of racial bias

But the fact that punishment is an expression of negative attitudes makes it risky. To begin with, not all negative attitudes toward others are justified.

Implicitly or explicitly, one may dislike members of a racial group or ethnic minority, or associate negative stereotypes based on gender or sexual orientation. These sources of negative attitudes pose two kinds of risks given the expressive function of punishment. The first risk is that implicit or explicit racial biases will be confused for justified negative attitudes when a criminal defendant is prosecuted and punished. The second is that punishments themselves, even when justified, could reinforce existing implicit and explicit biases.

To understand how these two risks work, take the over-representation of Black Americans in the criminal legal system. Recent data shows that, even though incarceration rates for Black men are the lowest they have been since 1989, they are still 5.8 times more likely to be incarcerated than white men.

Black defendants are not only more likely to be sentenced to death than their white counterparts, but also, once sentenced, they are more likely to actually be executed than white death row inmates.

The first risk plays a role in the over-punishment of Black Americans because in many cases, police, prosecutors, judges and juries confuse their unjustified negative feelings based on race for appropriate feelings of resentment based on a defendant having committed a crime. Thus, if they have negative attitudes toward a defendant because of race, a jury may find guilt where there is none, or over-punish.

Social scientists talk about this phenomenon when they explain that implicit biases or unconscious negative attitudes affect criminal justice outcomes, particularly for Black Americans. Implicit biases are at least one factor in why Black Americans are given harsher sentences than white criminals who commit similar crimes.

The second risk is more subtle. The message of punishment is that the criminal’s act is bad and so is the criminal. Seeing members of a marginalized racial or ethnic group punished could reinforce prejudicial negative attitudes.

Evidence of this second risk was recently demonstrated in a troubling study: The more white Americans learn that Black Americans are over-represented in the criminal justice system, the more they may seek increasingly punitive policies. Authors of the study linked this to pervasive implicit biases in which white Americans unconsciously associate Black faces with crime. Thus, punishing Black Americans strengthens an unjustifiable association between Blackness and criminality. This has a profound effect on the lives of all Black Americans, whether they ever commit a crime or not.

The risk of implicit biases

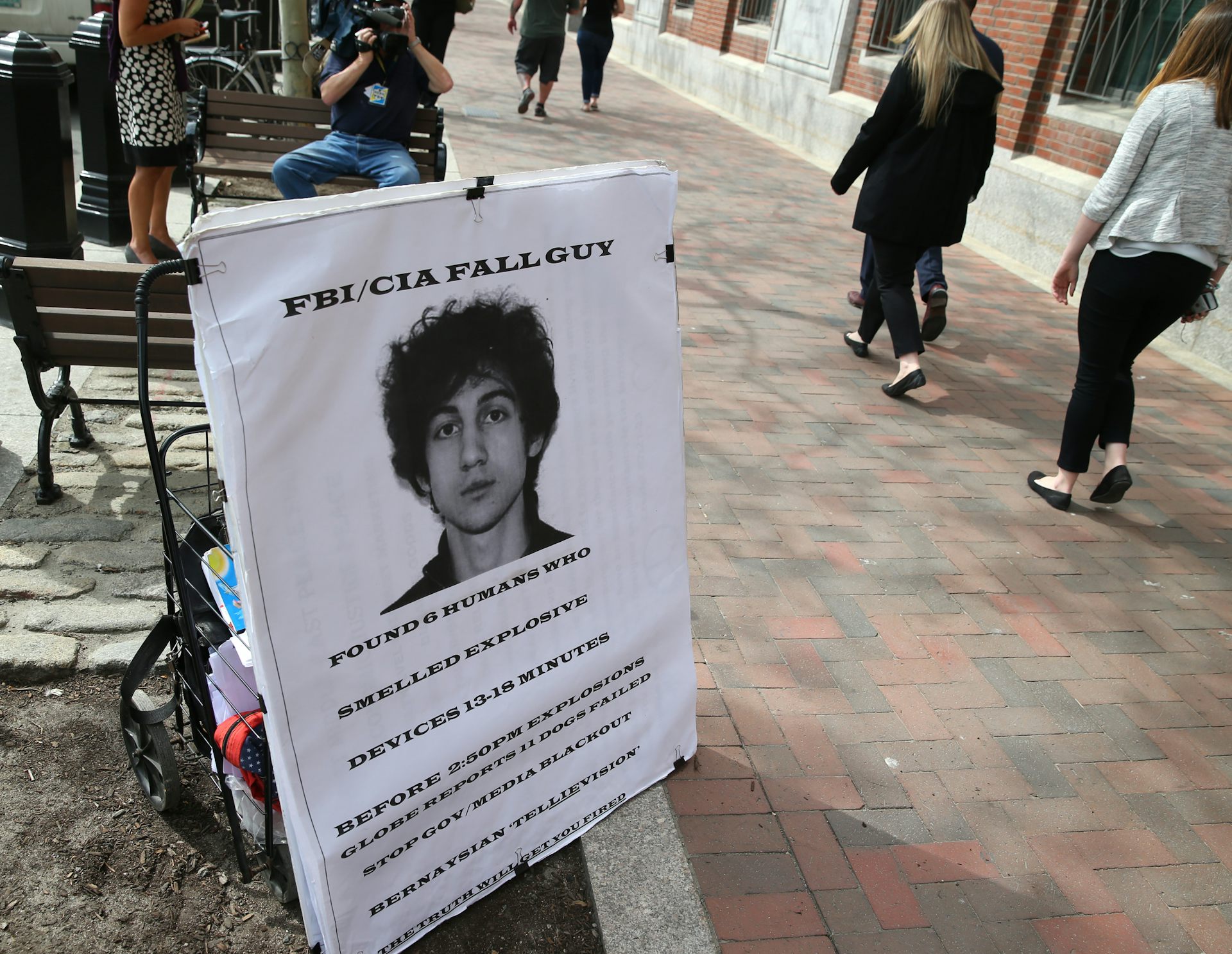

Tsarnaev is not Black. But he is Chechen, a majority-Muslim ethnic group from Eastern Europe.

In the United States, studies indicate that half to two-thirds of non-Muslim Americans hold anti-Muslim implicit biases. Legal scholar Khaled Beydoun explains that federal anti-terrorism projects since 9/11 have treated Muslims – and those assumed, based on their ethnicity, to be Muslim – as suspected terrorists based only on their perceived religion.

The growing implicit biases against Muslims and aggressive policing of Muslim communities already put American Muslims at risk of similar treatment in the criminal legal system as Black Americans.

These risks do not mean that the death penalty is never warranted or that it is not warranted in this case. But it does mean that policymakers and the public should take these risks into account when making laws and setting policies about punishing.![]()

Amelia Wirts, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.