The National Cybersecurity Strategy calls for new and harmonized cyber regulations. To succeed, there is a lot of homework left to do, starting with a better understanding of performance-based and other kinds of regulation.

Though the Biden administration’s new National Cybersecurity Strategy has much in common with previous guidance, it is breaking new ground in several areas, especially arguing for new regulation—since “the lack of mandatory requirements has resulted in inadequate and inconsistent outcomes.”

The White House’s goal is to prevent cyber incidents from disrupting their operations and avoid cascading impacts on the U.S. economy and national security. But which one of these regulations is better at achieving that?

-

“Identify, report, and correct information and information system flaws in a timely manner.“

-

“For patches and updates that are listed on CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog … and have a [severity score] of ‘Critical’ … the patch/update must be installed within 15 days of its availability …. All other updates and patches must be installed within 30 days of availability.”

The first, from the U.S. Department of Defense, provides regulated entities significant flexibility to implement broad security principles. But such vague guidance offers no suggestions on how serious a flaw needs to be to require fixing and just how long is “timely.” A company might patch the flaw in a month only to be punished because it wasn’t done in a week.

The second, from a now superseded U.S. regulation for pipeline operators, is strikingly specific. Entities won’t have much doubt about the regulator’s expectations, which could benefit less-mature cyber teams or those wanting to head off potential indictments after the fact by a crusading regulator. But others would feel handcuffed. Because it prioritizes patching the most severe vulnerabilities, this regulation is risk based, but that risk assessment is being made by others and not the entities themselves. Just because a vulnerability is rated as “critical” by someone else doesn’t mean it is critical to them, as they may have a rich set of additional countermeasures. Moreover, a company that successfully met these rigorous deadlines might not have any resources to reduce more critical risks.

The new U.S. National Cybersecurity Strategy puts such issues at the center of the cybersecurity debate by pushing for new regulations that are “performance-based” and agile, as well as tailored for each critical-infrastructure sector and “harmonized to reduce duplication.”

But what makes a regulation performance based? Are performance-based regulations always the best choice, or does tailoring for each sector mean some regulations should be focused on something other than performance? Are performance-based regulations easier to harmonize across regulating bodies and jurisdictions? There is very little research to guide policymakers in answering these questions. Fortunately, Jim Dempsey set an initial path for such research in an influential Lawfare article. During my time in the Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD), the article seemed to be on every relevant desk there. This article takes further steps down Dempsey’s path.

As it turns out, of the two regulations on patching mentioned above, the second one—with specific and measurable outcomes—is by far the more performance-based regulation. But such tightly prescriptive rules are likely not what the White House wanted to encourage. That regulation was superseded after cries for more performance-based regulation when, ironically, it was one of the most performance-based cyber regulations ever. What critics actually wanted was more management- or principles-based regulations.

Framework of Cyber Regulations

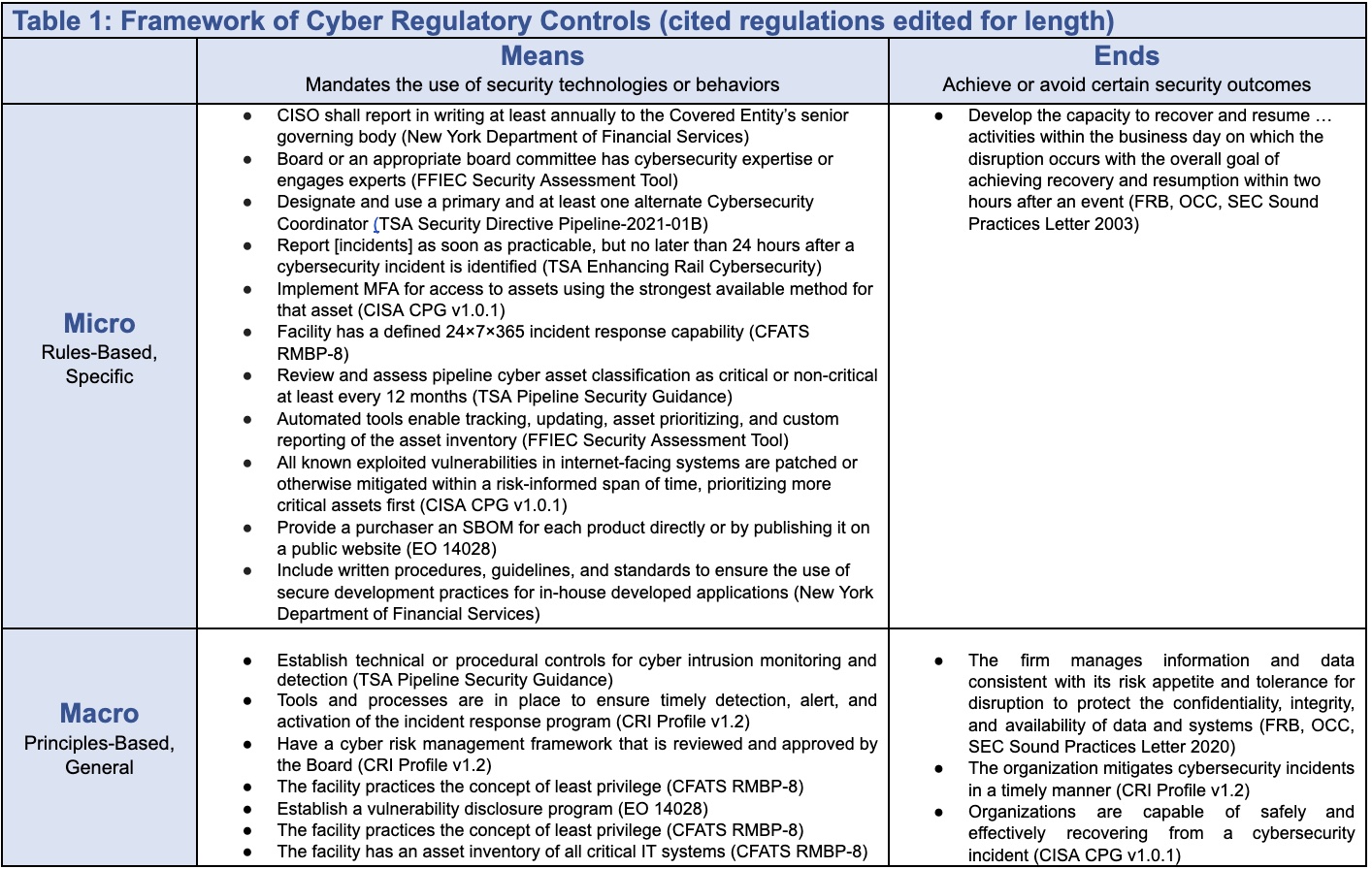

In the regulation of physical assets, there are two important distinctions: first by the types of commands (specifying either ends or means), and second by the breadth of their focus (as micro or macro). These are all broadly command and control regulations, meaning that the government specifies what regulated entities should seek or avoid rather than relying on tax incentives or self-regulation.

Cary Coglianese—in the canonical article describing this framework—clarifies that when regulators specify ends, they direct targets to achieve or avoid certain outcomes: For example, 10 grams of ground allspice cannot have more than 30 insect fragments or 1 rodent hair. Or in cybersecurity terms, select systemically important financial firms had to “achiev[e] recovery and resumption within two hours” after a disruptive event, according to a 2003 requirement.

Means, by comparison, regulate for some proxy for regulators’ actual goals by mandating or forbidding particular behaviors, processes, or technologies. A common cybersecurity means regulation is some version of having a “24 × 7 × 365 computer incident response capability for cyber incidents,” as is required for the chemical sector.

Micro-level regulations “require either the adoption of specific means or the attainment of concrete outcomes” while those at the macro-level include only the most general requirements. For example, the Transportation Security Administration’s regulation for the pipeline sector to classify their information-technology assets (“Review and assess pipeline cyber asset classification as critical or non-critical at least every 12 months”) is more micro than its similar rule for the chemical sector (“facility has an asset inventory of all critical IT [information technology] systems”). Perhaps this difference is due to differences in the risk profile of each sector, perhaps not.

Table 1 below has an initial 2 x 2 framework to distinguish means-ends and micro-macro with representative examples from cyber regulations of the past two decades.

Categories of Regulation and When to Use Which

This simple 2 x 2 chart simplifies the definition of performance-based regulation as compared to other types, allowing regulators to tailor regulations to the risks of their particular sector far more easily.

Performance-based regulations are micro-ends.

Also called outcome-based regulations, these are requirements to mandate, avoid, or achieve the specific outcomes that are the ultimate concern for the regulator. Recovery-time objectives, like the two-hour limit mentioned above for systemically important clearing and settling firms, are performance based: Regulators want a specific result (recovery and resumption of clearing and settling) in a specific time frame (two hours).

It’s not surprising that the National Cybersecurity Strategy encourages this model—as they specify a regulator’s desired outcomes. But a key characteristic of performance-based regulations is that they succeed “only if government agencies are able to specify, measure, and enforce performance,” in Dempsey’s words.

Unfortunately, cybersecurity is “immensely difficult to measure” because cybersecurity is not like allspice. Technology moves quickly, there are creative and motivated adversaries, and what worked yesterday won’t ensure success tomorrow. Recovery-time objectives are one of the few areas in cybersecurity where outcomes are easily measurable. Accordingly, it is one of the few existing performance-based cyber regulations since, for all their strengths, such regulations are often an unsuitable—or at least unavailable—choice for cybersecurity.

Even where measurement is possible, it may not be optimal—as a performance-based regulation may reduce flexibility. As mentioned above, giving pipeline operators just 15 days to patch critical vulnerabilities is measurable but far too specific. Patching at scale is complex, and only a small fraction of vulnerabilities are ever exploited: Such strict deadlines can undermine security by tying up resources that could be used to address more severe risks.

Performance-based regulations like recovery-time objectives are, according to Coglianese, most appropriate for sectors that are broadly homogeneous; that is, they are similar and stable over time. They may be more suitable, for example, for the pipeline sector, where companies are relatively similar and stable, than for fast-changing and diverse sectors such as fintech.

To summarize: Performance-based regulations are most suitable where outputs can be measured for mostly homogeneous, stable sectors and entities.

Management-based regulations are the opposite of performance-based: macro-means.

These kinds of regulations mandate general planning and management practices; whereas a performance-based regulation would mandate recovery within two hours, a management-based regulation might only require the company to have an appropriate recovery plan. Such requirements are especially useful when outcomes can’t be measured but the regulator still wants to reduce specific risks. This is the case for the majority of cybersecurity contexts where “many things can’t be measured, but some processes really, really help,” as Columbia cybersecurity professor Steven Bellovin commented when reviewing a draft of this article.

There are many such cyber regulations: “Establish technical or procedural controls for cyber intrusion monitoring and detection,” as called for in pipeline regulations or “Tools and processes are in place to ensure timely detection, alert, and activation of the incident response program,” per the Cyber Risk Profile for the finance sector. While such regulations can still be quite specific and mandatory, they are still more general than performance-based regulations. They neither dictate specific technologies or controls, for example, nor specify how serious an incident needs to be before it triggers a response.

“Management-based regulation is worth considering any time the government confronts hard-to-assess risks generated by many diverse firms,” advises Coglianese. Accordingly, for cybersecurity it may be a better fit than performance-based regulations as technology is constantly changing.

Principles-based regulations are macro-ends.

A primary goal of principles-based regulations is to “give regulated entities flexibility in how best to achieve a desired objective,” according to Heath Tarbert, then-head of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. They are macro-ends.

Compare these two regulations: “Tools and processes are in place to ensure timely detection, alert, and activation of the incident response program,” and “The organization mitigates cybersecurity incidents in a timely manner.” Both come from the same document—the Cyber Risk Profile for the finance sector—and are macro. But the first regulates means (tools and processes) and is management-based, while the second regulates ends (successful, quick mitigation) and is accordingly principles-based.

Tarbert noted several strengths of principles-based regulation:

-

“generally promotes a more flexible regulatory approach”;

-

“enhances the responsiveness of regulation to market innovation and other developments [and] … can help ‘future proof’ regulatory requirements”;

-

“discourage ‘loophole’ behavior and ‘checklist’ style approaches to compliance with the law”;

-

“encourages the more direct involvement of C-suite or other senior management rather than relying on lower ranking compliance personnel”;

-

“can lower compliance costs”;

-

can encourage innovation by facilitating “the development of new business models, products, and internal processes”; and

-

“helps to promote comparability and convergence among international regulators. While different national regulators rarely agree on specific, granular rules … they nonetheless frequently can reach consensus on principles.”

This last strength makes principles- and management-based regulations particularly relevant for harmonization. It is far easier to harmonize global financial regulations when they are as broad as this rule by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada: “Timely response, containment and recovery capabilities are established.”

Principles-based cyber regulations are less measurable than performance-based ones, since they are more general, and each regulated entity is responsible for meeting the goals as they think best. Two “sound practices” letters from U.S. financial regulators illustrate the difference. Whereas in 2003, the regulators specified the goal of “recovery and resumption within two hours,” by 2020 a similar letter called on the boards of financial firms to determine their own tolerance for disruption and ensure operational processes met that goal.

Principles-based regulations are a particularly good fit for sectors like finance, which are more likely to have mature teams able to translate the broad regulatory outcome into entity-specific behaviors and measure compliance. The result may still lead to compliance checklists, but at least they are checklists of a firm’s own design.

Critically, principles-based regulation requires a robust system of external oversight, coupled with post-hoc enforcement of the rules—such as the extensive structure built for the finance sector. Proper cybersecurity oversight that could adequately accommodate principles-based regulation would require a substantial investment to create or expand government cyber-regulatory agencies or the creation of self-regulatory organizations, an idea proposed in class by Columbia students.

Rule-based regulations complement principles-based regulations: micro-level and either means or ends.

Rules-based regulation can have a bad reputation as a mere compliance exercise that doesn’t reduce risk and only produces ineffectual and endless checklists. But performance-based regulation, as called for in the National Cybersecurity Strategy, is a form of rule-based regulation.

An advantage of prescriptive rules, compared to principles, is that they can provide greater clarity with regulators and defend more effectively against private litigation. For example, clearing and settling firms may have thought a government-mandated recovery-time objective of two hours was unwarrantedly quick. But it is a far clearer objective than that stated in the Cyber Risk Profile (“The organization mitigates cybersecurity incidents in a timely manner”) or the requirement of the Canadian financial regulator (for “timely response, containment and recovery”). A firm may consider its eight-hour mitigation to have been exceptionally prompt, only to be fined retrospectively by a regulator with different expectations.

As I had a chief information security officer (CISO) tell me recently, companies may not want specific cyber regulations, but CISOs do. Though rules may constrain CISOs, they do give more objective measures of success to ensure they are not indicted for having insufficient internal controls.

A rules-based approach, according to Tarbert, “is most effective when regulators are able to adopt rules that can endure”—remaining relevant despite changes in business models, customer demands, and technology. While it may sometimes seem that cybersecurity threats and technology are changing too quickly to have rules that endure, in fact there are many examples:

-

Applications running executable code should be disabled by default on all information technology and operational technology assets to reduce the risk of malware (Cybersecurity Performance Goals, v 2022).

-

The institution belongs or subscribes to a threat and vulnerability information sharing source(s) that provides information on the threat (FFIEC Security Assessment Tool).

-

The CISO of each Covered Entity shall report in writing at least annually to the Covered Entity’s board of directors or equivalent governing body (New York Department of Financial Services, 23 NYCRR Part 500).

-

The facility has an asset inventory of all critical IT systems (CFATS for the chemical sector).

-

Use administratively separate build environments (Executive Order 14028 for entities selling to the U.S. government).

Checklists may get demeaned, but they are an effective tool to ensure success on repetitive and complex tasks.

Moving Forward

The framework in Table 1 is only an early effort to apply the lessons from regulating physical assets, building on the earlier excellent work of Dempsey. But even this early work lays enough of a foundation to make several suggestions.

First, as they work to harmonize existing regulations and develop new ones, regulators should assess whether such rules are micro or macro, and ends or means. There can be good reasons for a regulation to have controls in different quadrants: Some might be more measurable (and so performance based) while others are not and need to specify processes (management based). But some controls are in different quadrants simply because until now there hasn’t been a simple table with such quadrants. Either way, regulators should review which rules fit where and why.

Second, the ONCD should work with sector risk-management agencies, regulators, and chief economists to use this framework to determine the best type of regulation for their sector, leveraging the assessment of market failures. A rules-based approach is probably better for the water and waste-water sector, which is relatively stable, and where one regulated entity looks much like the rest. Regulations for the finance sector—fast moving, heterogeneous, and where firms are deeply experienced in tracking their own compliance and regulated by many entities—should be more based on principles.

Third, to maximize chances for harmonization, regulators should aim for principles-based regulations that are more amenable than those with more specific rules. After principles are agreed upon, aligning the more exact rules, if necessary, can come later with more experience and trust.

Fourth, the ONCD should begin coordinating a new cyber-regulation strategy. Regulation is the most important, complex, and politically sensitive cyber project ever undertaken by the federal government. Unlike other topics, such as workforce and education, regulation is so politically sensitive that the ONCD has just one shot to get this correct. If it fails now, future administrations will likely not take it on again for a decade.

This strategy, or perhaps a less formal road map, would slot underneath the National Cybersecurity Strategy to coordinate the full range of regulatory work—which includes harmonizing existing regulations, establishing minimum security baselines for critical infrastructure, pushing for software liability, exploring options for regulations for platforms or major service providers, and continuing other important work referenced above. These are critical and complex issues that are at the core of the role of government in a free society. They deserve a single strategy, signed off by deputies or principals of the National Security Council and National Economic Council.

A regulatory strategy or road map could be substantially harder to coordinate than the recent strategy on cyber education and workforce, as so many of the regulatory agencies involved in this context are independent and cannot be bound by such a document. Moreover, the year before a new presidential election may not be the best time for such a politically sensitive and difficult strategy.

Fortunately, the Forum for Independent and Executive Branch Regulators, led and newly reinvigorated by Jessica Rosenworcel, the chair of the Federal Communications Commission, has already been making strong progress. The right process for a strategy or road map should reinforce rather than compete with this effort.

Cyber regulation is needed because the markets have failed to deliver security. The government and outside researchers still have a lot of homework to do to ensure regulations are correctly targeted for the best chance of success with the least cost of compliance. This framework, built by relying on Dempsey, who himself relied on Coglianese, Tarbert, and others, is an important next step.

–

Jason Healey is a Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University’s School for International and Public Affairs and founder of the global “Cyber 9/12” student cyber-policy competition. He is also a part-time strategist at the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and edited the first history of conflict in cyberspace, “A Fierce Domain: Cyber Conflict, 1986 to 2012.” He has held cyber positions at the White House, Goldman Sachs, and the U.S. Air Force.

– Published Courtesy of Lawfare