A war between the United States and a capable, nuclear-armed adversary would introduce the risk of destruction on a scale the United States has not seriously contemplated since the end of the Cold War. The main debate in the policy world is between advocates of theories of victory that are reliant on denial and advocates of theories of victory that depend on cost imposition. Cost-imposition strategies, such as those requiring a distant blockade or a punitive air campaign, require the United States to successfully navigate what the authors refer to as the Goldilocks Challenge: specifically, identifying with high confidence a “sweet spot” of pressure points that are valuable enough to influence enemy decisionmaking but not so valuable that they cause unacceptable retaliation.

To help the U.S. Air Force evaluate the feasibility of a cost-imposition strategy and assess the associated risks of uncontrolled escalation, the authors examine the ability of past decisionmakers to identify adversary thresholds and to apply this information to control escalation during militarized crises between nuclear-armed states.

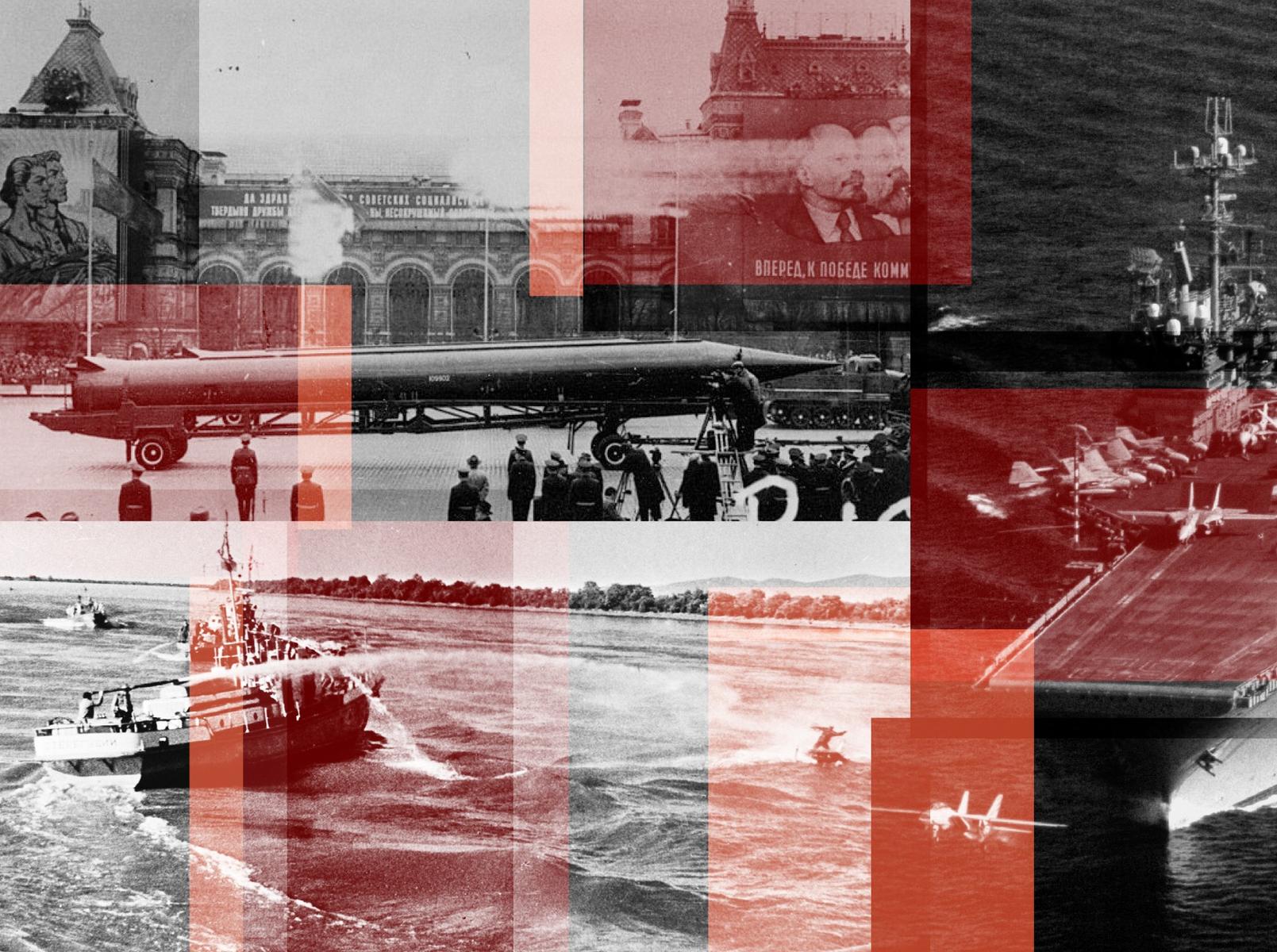

The authors analyze three historical cases of militarized crises and conflicts between nuclear-armed major powers: (1) the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis between the United States and the Soviet Union, (2) the 1969 border conflict between China and the Soviet Union, and (3) the 1995–1996 crisis between the United States and China over Taiwan.

Key Findings

- The United States will have a limited ability to control how adversaries interpret its coercive actions. Adversaries may wrongly surmise U.S. intentions from uncoordinated, unauthorized, or unrelated policies or actions—and vice versa.

- Decisionmakers may not immediately recognize that a crisis or conflict has begun. Delays can impede the transmission of coercive signals, skew assessments of adversary resolve and valuation of targets, and limit parties’ ability to avert or control escalation.

- Decisionmakers’ assessment of the value of a target or the significance of a threat may change over time as a conflict evolves and potential costs become clearer. This suggests that the boundaries of any sweet spot within the Goldilocks Challenge framework will be fluid, increasing the prospect of inadvertent escalation.

- The reorganization or creation of decisionmaking bodies may alter access to or interpretation of information, complicating efforts to sway power centers. Changes in the composition or procedures of such forums may change the balance of influence among leaders and contribute to unpredictable outcomes.

- A perceived loss of control over the intensity, pace, or scope of a confrontation might not compel a rival to capitulate. Leaders may respond in unpredictable ways to unanticipated escalation or a loss of battlefield or theater awareness.

- Nuclear threats may increase adversary fears without compelling substantial changes in behavior. In all three cases studied, an inferior nuclear power antagonized a more powerful rival. Varied attitudes toward the utility of nuclear weapons for warfighting may make some leaders more tolerant of nuclear threats.