The two attempted assassinations targeting Trump are part of a much broader trend targeting candidates for office.

Editor’s Note: The repeated assassination attempts targeting Donald Trump have highlighted the risk of political violence in the United States, but the threat goes far beyond attacks on the former president. The Council on Foreign Relations’s Jacob Ware points out that the United States is already neck deep in election-related violence and details the range of dangers and why the situation may get even worse. – Daniel Byman

***

In May, an Atlanta concert was targeted by a white supremacist would-be terrorist who traveled from Arizona hoping to spark a “race war” prior to the 2024 presidential election. He was apprehended somewhere in New Mexico while traveling cross country. Two months later, in Michigan, an 80-year-old man placing Trump yard signs was run over by an ATV. The assailant also damaged two cars displaying pro-Trump and pro-law enforcement stickers.

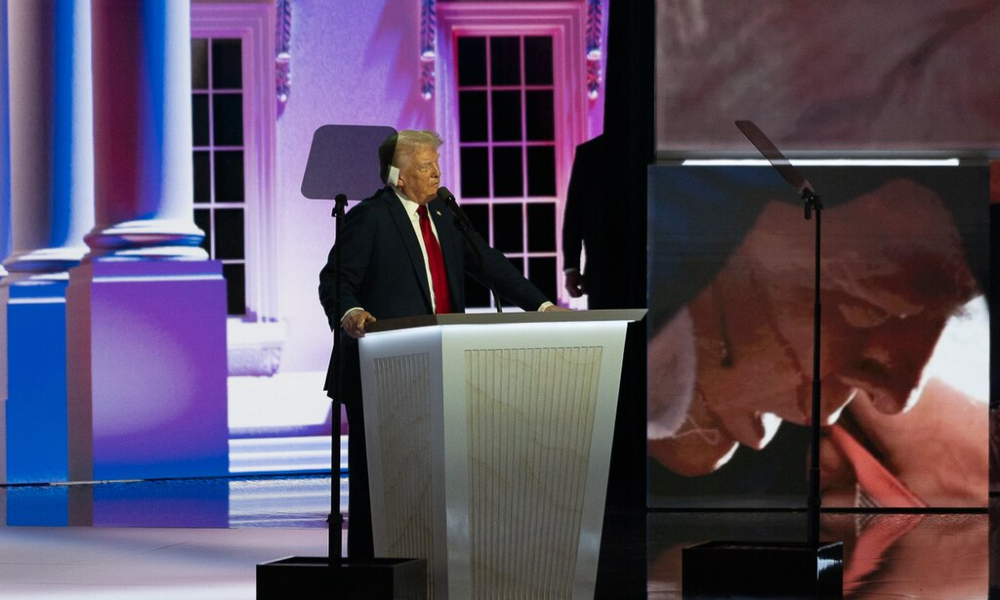

Many political figures daring to run for public office have similarly found themselves in the crosshairs over the past several months. Former President Donald Trump has been targeted in several assassination plots, including two that involved an actual exchange of gunfire (Trump was wounded in the first of these attacks in July). Vice President Kamala Harris, too, has found herself on the end of violent threats. In Virginia, a 66-year-old man was arrested for threats against the candidate, including the ominous warning that he had his “AR-15 LOCKED AND LOADED.” (Several additional incidents have been brought to light through Seamus Hughes’s outstanding Court Watch newsletter.)

Local election officials have also been targeted. Battleground counties, such as Cobb County in Georgia and Maricopa County in Arizona, have been unable to protect their volunteer election workers from a torrent of threatening communications, and in recent days election offices in more than 20 states have received suspicious packages from a group calling itself the “United States Traitor Elimination Army.” At least some of these packages contained a white substance, though so far authorities believe this to be benign. According to the Associated Press, some voting centers have introduced bulletproof glass and panic buttons in an effort to improve security. Last October, terrorism experts Seamus Hughes and Pete Simi called this development “the slow burn threatening our democracy.” They date the rise in threats to public officials to 2016, when Trump roared onto the political stage.

Assassination threats are not new, having blighted both the domestic and international political landscape for years now. Nor is domestic terrorism, which has become a major national security concern over the past several years. But counterterrorism scholars and analysts have predicted for months that the 2024 presidential election would provide a particularly volatile flashpoint for election violence. The near-assassination of Trump demonstrates the accuracy of these concerns—but they are only part of the story. A month from the election itself, election violence is already in full swing, and the only reason the carnage has not been worse is good police work and better luck.

Lessons Learned, a Month Out

If there is any silver lining to this early violence, it is that it has already revealed a set of important themes and trends that may help law enforcement prevent future acts of violence. First, the primary threat, at least in the pre-election period, appears to be targeted against politicians and other public officials. This development has been building for months and explains candidates such as Nikki Haley and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. requesting Secret Service protection. Hughes and his team at the University of Nebraska-Omaha’s National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology, and Education (NCITE) Center of Excellence have found that “authorities made 112 arrests for threats against public officials this year, which broke the previous record of 90 arrests in 2023.” This record has been set before general-election voting has even begun. Importantly, this trend spans the political divide—although threats do seem to be targeted more at Democrats than Republicans. In Tennessee, for instance, a 37-year-old man was arrested after he “threatened to kill, assassinate, shoot, and crash the plane of President Biden; assassinate Vice President Harris; and assassinate former President Obama.”

The early focus on elected officials and candidates is not surprising; as I predicted in April in a Council on Foreign Relations report on “Preventing U.S. Election Violence in 2024,” the pre-election period was likely to be characterized by assassination threats against candidates because they represent the most overt and obvious symbols of our political unrest. (My other fears—threats to the party conventions and violence related to Trump’s court process—have not materialized.) As early voting begins, we should prepare for extremist crosshairs to shift toward polling places and vote-tallying centers. Depending on the results, the post-election period will most likely be marked by threats to government infrastructure symbolizing the continued functioning of U.S. democracy—a threat demonstrated previously by the extremists who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Second, the 2024 election violence appears to conform with broader trends in terrorism. The assailants are acting alone, and social media appears to be playing a significant role in their radicalization. As my co-author Bruce Hoffman and I lay out in our book, “God, Guns, and Sedition: Far-Right Terrorism in America,” social media radicalization and lone-actor terrorism, both pioneered by former KKK leader Louis Beam in the late 20th century, constitute arguably the two most significant innovations in terrorism history, allowing extremists to effectively operate without detection by law enforcement. Such was the challenge with both threats against Trump. In addition, the threats have often been issued against so-called soft targets associated with the candidates and their party. In Florida, for instance, a 60-year-old woman promised to detonate an explosive at Trump International Golf Club—the same club where Ryan Wesley Routh tried to shoot Trump on Sept. 15. The woman also threatened Trump International Hotel in Las Vegas.

Third, sometimes election violence does not require a distinct partisan ideology. A Kansas City man arrested for posting TikToks threatening law enforcement and Republicans had a profile picture stating “Fuck ‘em both ‘24.” A similar dynamic was seemingly at play with the two shootings intended to kill Trump. Investigators have not identified an ironclad partisan motive in either case. Routh voted for Trump in 2016 and seems to have been driven largely by his support for Ukraine, while Thomas Matthew Crooks had also researched Biden as he prepared for the shooting. Simi and Hughes came to a similar conclusion in their report last year, noting that of the “more than 500 individuals … charged in federal court in the past 10 years for making threats against public officials … more than half of them did not express an explicit ideological motivation.”

Finally, the heightened threat environment provides a unique opportunity for America’s foreign adversaries. Iran, for instance, has promised to assassinate Trump in retaliation for the U.S. strike against Iranian military leader Qassem Soleimani in January 2020. In a self-published book, Routh wrote a direct address to Iran, stating, “You are free to assassinate Trump,” and indeed, in July, U.S. officials arrested an Iran-linked Pakistani man for plotting to assassinate the former president. Attorney General Merrick Garland noted, “[W]e expect that these threats will continue and that these cases will not be the last.” Foreign adversaries may also be capitalizing on fears of political violence to stoke division. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine has said that some of the threats targeting the Haitian community in Springfield have come from abroad.

A Security Dilemma

Any optimism regarding the next month will require proper contextualization. Election violence has been a persistent feature of U.S. politics, and while it has escalated in recent years, the country has shown remarkable resilience. In 2022, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi was targeted in an assassination attempt that involved an assailant seriously wounding her husband, Paul. Biden’s inauguration in January 2021 showcased America’s resilience to the horrendous events that occurred at the U.S. Capitol 14 days before. That cycle also saw an attempted kidnapping of Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. In 2018, no fewer than four terrorist attacks occurred in the 10 days before the election, all linked to the violent far right. Most notably, the deadliest act of anti-Semitic terrorism in U.S. history killed 10 at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, and a Florida-based Trump supporter dispatched faulty mail bombs to several Democratic leaders. Earlier generations witnessed the shootings of presidential candidates Robert F. Kennedy, George Wallace, and Huey Long. The United States and its institutions persevered then and will probably do so again.

To many, however, this election feels different. In large part, that is due to the nation’s crippling polarization and partisanship, which greatly complicates a cohesive response to election violence. Indeed, we find ourselves in a spiraling security dilemma: Because the Biden administration carries such little legitimacy among its opponents, the measures the administration might wish to take to combat election violence would likely be perceived as preparation for further electoral fraud. Good-faith efforts to reduce tensions and respond to threats, such as digital literacy programming to protect the public from disinformation, efforts to ensure transparency in the vote-counting process, and possibly the stationing of greater law enforcement resources at key sites, would likely be seen Democratic propaganda and means to persecute Republicans. Without the legitimacy to chip away at the narrative that Democrats win elections only through cheating, a Harris victory would only affirm right-wing extremists’ confirmation biases and embolden them to action—up to and including violence.

The Department of Homeland Security recently designated Jan. 6, 2025, as a National Special Security Event, opening up new resources and placing the Secret Service as the lead agency. Additionally, law enforcement has conducted trainings to prepare for possible threats at various locations. Those steps will likely strengthen the defensive counterterrorism posture against violence. However, some of the more strategic countermeasures that might prevent or complicate violence in the longer term—gun control, for instance, or efforts to reverse the sequence of vote-counting in some states to prevent the “red mirage”—will not be implemented in time for the election.

In other words, a violent storm is already lashing our shores and shows no sign of relenting, and there is very little that authorities can do to stop it.

– Jacob Ware is a research fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and an adjunct professor in Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. Published courtesy of Lawfare.