When nature vanishes, people of color and low-income Americans disproportionally lose critical environmental and health benefits—including air quality, crop productivity and natural disease control—a new study in Nature Communications finds.

The University of Vermont research is the first national study to explore the unequal impacts on American society—by race, income and other demographics—of projected declines in nature, and its many benefits, across the United States.

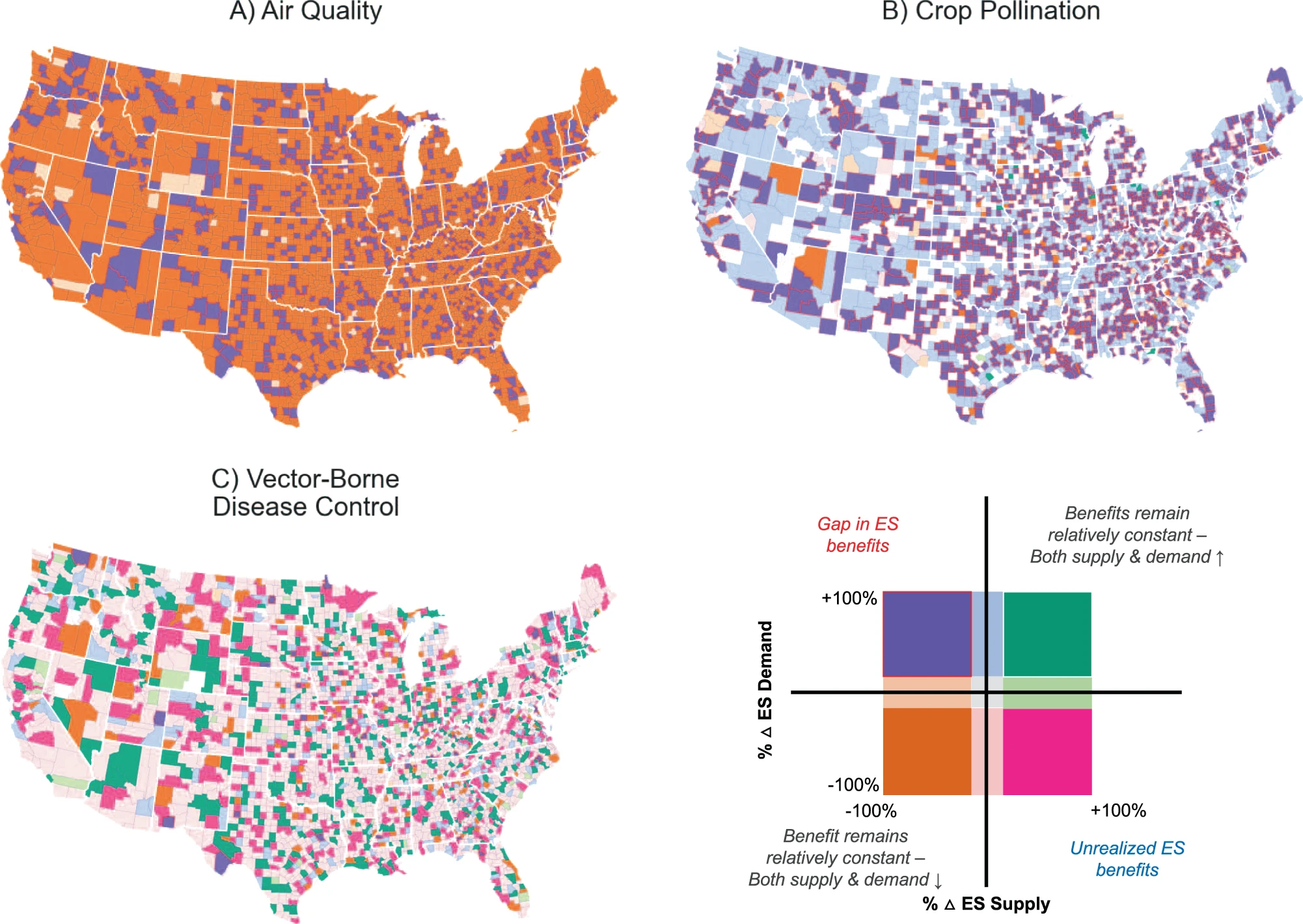

Focusing on three vital ecosystem services—air quality, crop pollination, and control of insect-borne disease (West Nile virus), researchers project that these benefits of nature will decrease for non-white people by an average of 224%, 118% and 111% between 2020 and 2100.

Researchers used advanced modeling to calculate changes in the distribution of these benefits by race, income levels, and population density (rural, urban, suburban).

“Given current and historical inequality in this country, our goal was to identify how future losses of nature might affect these racial and income disparities,” says UVM researcher Jesse Gourevitch. “Unfortunately, we find that, in general, non-white, lower-income, and urban populations disproportionately bear the burden of declines in ecosystem benefits.”

Opposing trends

Experts agree that in the future, urban populations are expected to grow, while rural populations shrink, and demographic groups become more segregated. Declines in nature will be largely driven by the conversion of forests and wetlands to cropland and urban development.

According to the study, land-use conversion trends are likely to be stronger in counties where marginalized populations are expected to grow. As a result, people of color are predicted to lose nature’s benefits, while white communities are projected to see gains. Black and Hispanic people are expected to experience a substantial loss of benefits, in particular.

Among income groups, counties with the lowest per capita income are expected to experience the greatest losses in air quality and West Nile virus protection—while these benefits increase significantly in high income counties.

“By paying attention to race and income—which are often overlooked in environmental research—we can help leaders address inequities in their policy decisions, so that nature’s benefits are distributed more equitably in the future,” says UVM Prof. Taylor Ricketts, a global expert on measuring nature’s benefits.

Troubling mismatches

Geographically, the study predicts significant “mismatches” between ecosystems benefits and human needs. For example, the team finds major declines in air quality and disease controls in urban counties where populations are expected to grow. Similarly, the researchers find steep declines in crop pollination—which is vital for farming—in rural areas, where agricultural productivity is most essential.

Beyond simply highlighting social and environmental problems, researchers say that targeted land use policies that factor in equity are needed to avoid exacerbating inequality in the U.S. These findings could also help to facilitate compensation for losses of nature’s benefits among marginalized groups, they say.

“To be clear, these results don’t imply that the U.S. is moving from an equitable baseline to an inequitable future,” says UVM co-author Luz de Wit. “Today’s inequities underpin the future disparities we estimate. For instance, Black and Hispanic people are currently disproportionately exposed to air pollution. That disparity, and others, are only expected to worsen in the future, without action.”