At just a few atoms of thickness, 2D materials offer revolutionary possibilities for new technologies that are microscopically sized but have the same capabilities as existing machines.

Florida State University researchers have unlocked a new method for producing one class of 2D material and for supercharging its magnetic properties. The work was published in Angewandte Chemie.

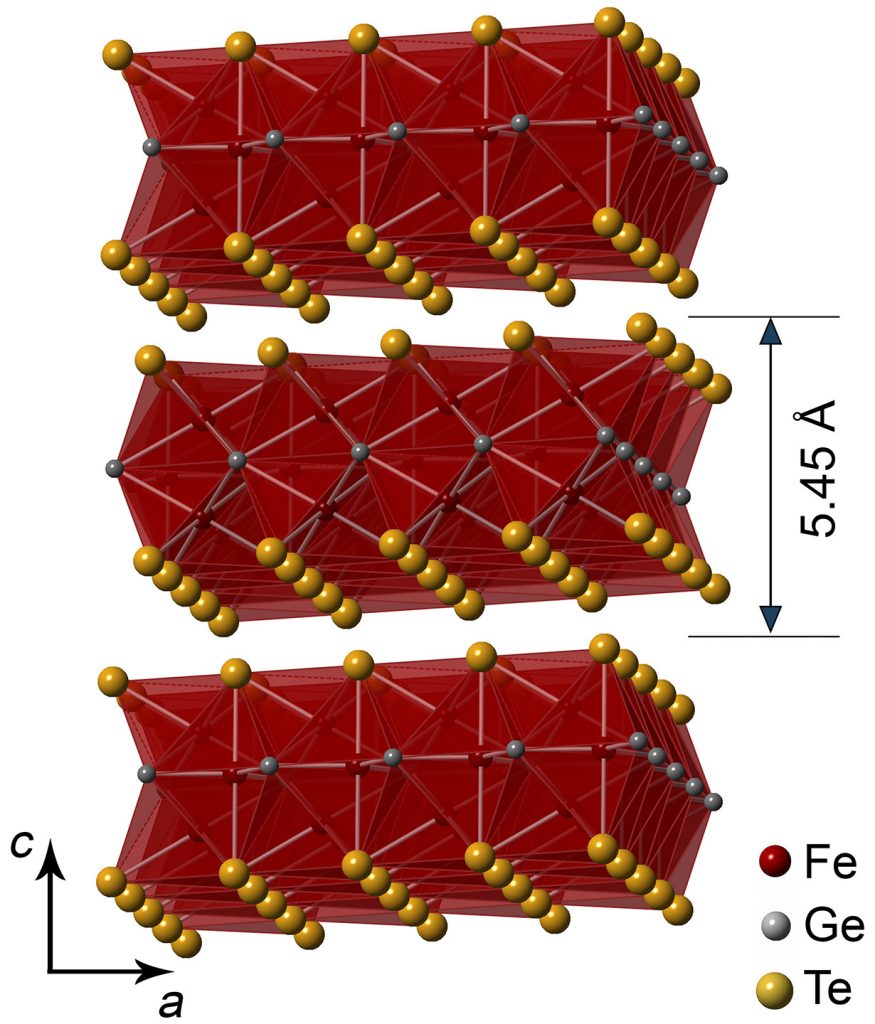

Experimenting on a metallic magnet made from the elements iron, germanium and tellurium and known as FGT, the research team made two breakthroughs: a collection method that yielded 1,000 times more material than typical practices, and the ability to alter FGT’s magnetic properties through a chemical treatment.

“2D materials are really fascinating because of their chemistry, physics and potential uses,” said Michael Shatruk, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry who led the research. “We’re moving toward developing more efficient electronic devices that consume less power, are lighter, faster and more responsive. 2D materials are a big part of this equation, but there’s still a lot of work to be done to make them viable. Our research is part of that effort.”

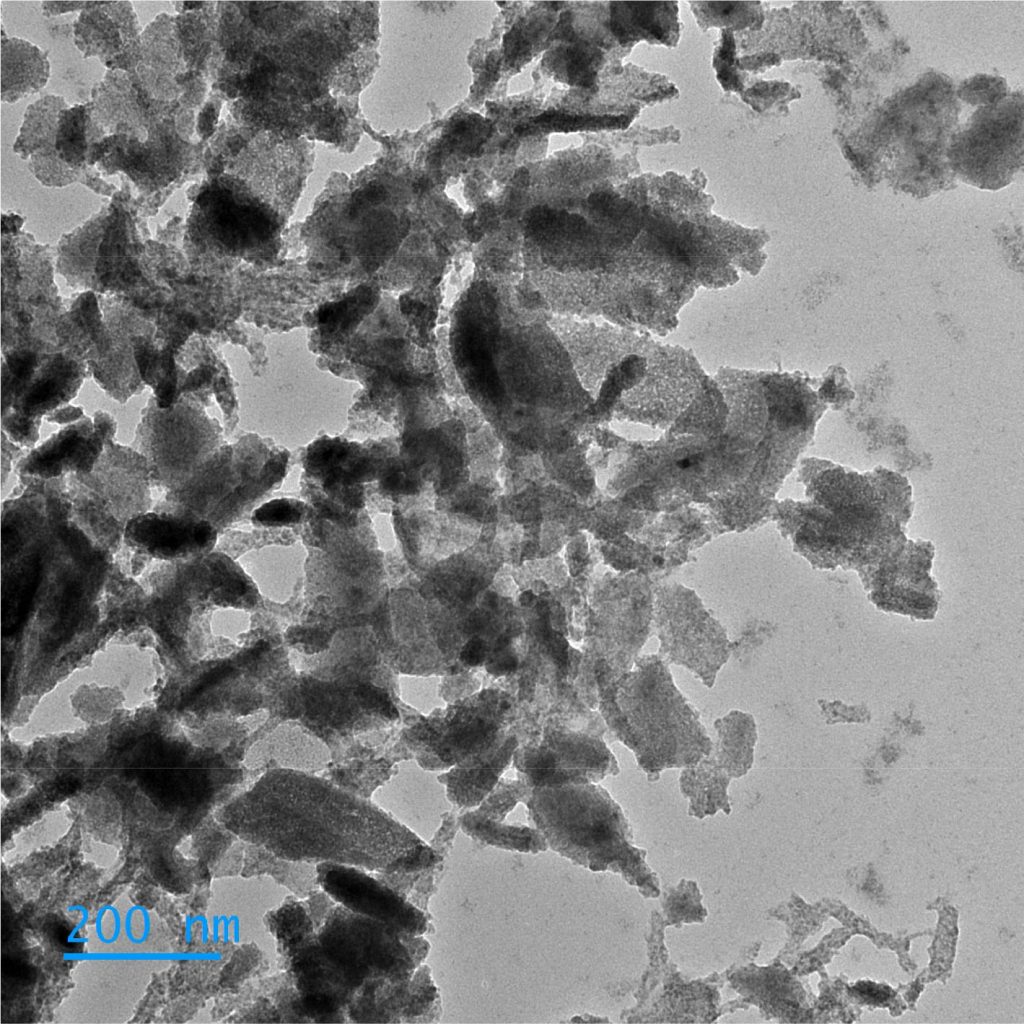

The research started with liquid phase exfoliation, a solution-processing technique that produces two-dimensional nanosheets from layered crystals in large quantities. The research team saw that other chemists were using this method to synthesize 2D semiconductors. They decided to apply it to magnetic materials.

Liquid phase exfoliation allows chemists to collect much more of these materials than would be possible through a more widespread technique of mechanical exfoliation that uses tape in the collection process. In Shatruk’s case, it allowed researchers to gather 1,000 times more materials than in the mechanical exfoliation methods.

“That was the first step, and we found that it was pretty efficient,” Shatruk said. “Once we did the exfoliation, we thought, ‘Well, exfoliating things seems easy. What if we applied chemistry to these exfoliated nanosheets?’”

Their success with exfoliation produced enough FGT for further exploration into the material’s chemistry. The team mixed the nanosheets with an organic compound called TCNQ, or 7,7,8,8-Tetracyanoquinodimethane. This process created a new material, FGT-TCNQ, through the transfer of electrons from the FGT nanosheets to the TCNQ molecules.

The new material was another breakthrough — a permanent magnet with higher coercivity, a measure of a magnet’s ability to withstand an external magnetic field.

The best permanent magnets used in the state-of-the-art technologies withstand magnetic fields of several Tesla, but achieving such resistance with 2D magnets like FGT is much more challenging, because the magnetic moment in the bulk material can be flipped with almost a negligible field — that is, the material has nearly zero coercivity.

Exfoliation of FGT crystals to nanosheets yielded a material with coercivity of about 0.1 Tesla, which is not high enough for many applications. When the FSU researchers added TCNQ to the FGT nanosheets, they increased the coercivity to 0.5 Tesla, a five-fold increase and very promising for potential applications of 2D magnets, for example, for spin filtering, electromagnetic shielding or data storage.

Unlike electromagnets, which need electricity to maintain a magnetic field, permanent magnets possess a persistent magnetic field on their own. They’re crucial components in all sorts of technology, such as MRI machines, hard drives, cell phones, wind turbines, loudspeakers and other devices.

The researchers plan to explore the possibility of treating materials through other methods, such as by gas transport or by exfoliating the molecular layer of TCNQ or similar active molecules and adding it to the magnetic material. They’ll also examine how such treatment might affect other 2D materials, such as semiconductors.

It’s an exciting finding, because it opens up so many paths for further exploration,” said doctoral candidate and co-author Govind Sarang. “There are a lot of different molecules that can help stabilize 2D magnets, enabling the design of materials with multiple layers whose magnetic properties are manipulated to enhance their functionality.”