Imagine the morning of Wednesday, Nov. 4, 2020. Given the unprecedented number of mail-in votes this election, Americans may wake up and still not know who won the presidential contest between Republican President Donald J. Trump and Democratic challenger Joseph Biden.

The contest could be so close that a result can’t be known until mail-in ballots in several key states, perhaps Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan or Florida, can be fully counted.

It’s conceivable that either candidate will refuse to accept the result, whether before or after the counting of absentee or mail-in ballots. That could lead to several lawsuits to stop the counting, to keep counting or to force a recount.

Amid what will likely be a flood of charges, countercharges and a lot of heated rhetoric from campaigns and supporters, there are prescribed legal processes that will play out in the event of election challenges. Here is how that will likely work.

Where challenges begin – and often end

With only a few exceptions, states run elections. By virtue of Article 1, Section 4 of the Constitution, state law governs almost every facet of the electoral process, including most aspects of voter eligibility, the location and hours of polling places, candidate access to the ballot and the members of the state’s Electoral College.

Consequently, electoral challenges must begin – and often will end – in state courts, which will apply that state’s laws.

A candidate who wants to challenge the result in any particular state must first identify what provision of state law the election did not satisfy. In a closely contested national election, where the results in some states are in doubt and may be for many days, this will likely result in several cases being filed simultaneously in several states, and by both major party candidates.

Congress has also provided that each state must have a mechanism for resolving any disputes that arise and that the state’s determination “shall be conclusive.”

In most cases, this means that state law, as interpreted and applied by state courts, will determine which candidate wins that state’s electoral votes.

Ordinarily, a decision by a state’s highest court about how to apply a state law cannot be appealed to a federal court. In such a case, the final decision in an election challenge rests with the state’s supreme court.

How to get to federal court

As seen in the 2000 case of Bush v. Gore, however, there are times when a federal court can hear an election-related case.

For a contested election case to be taken up by a federal court, there must be an allegation that federal constitutional rights, such as 14th Amendment claims to equal protection or due process of law, have been violated.

Similarly, if a person alleges that their right to vote was abridged because of their race or color, that case would be heard in a federal court under the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which is based on the 15th Amendment.

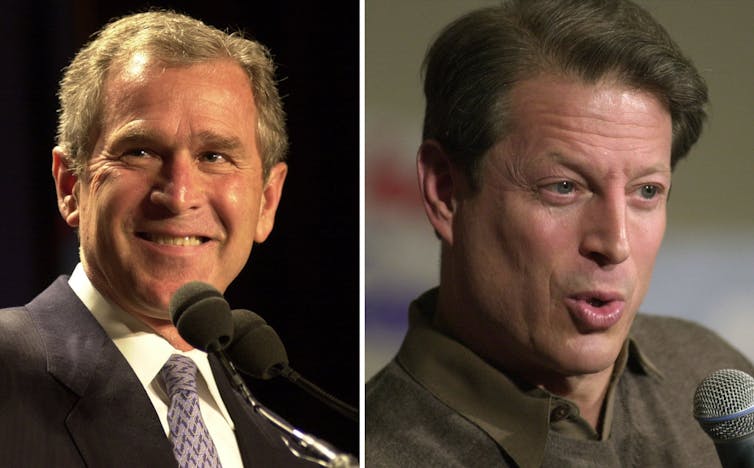

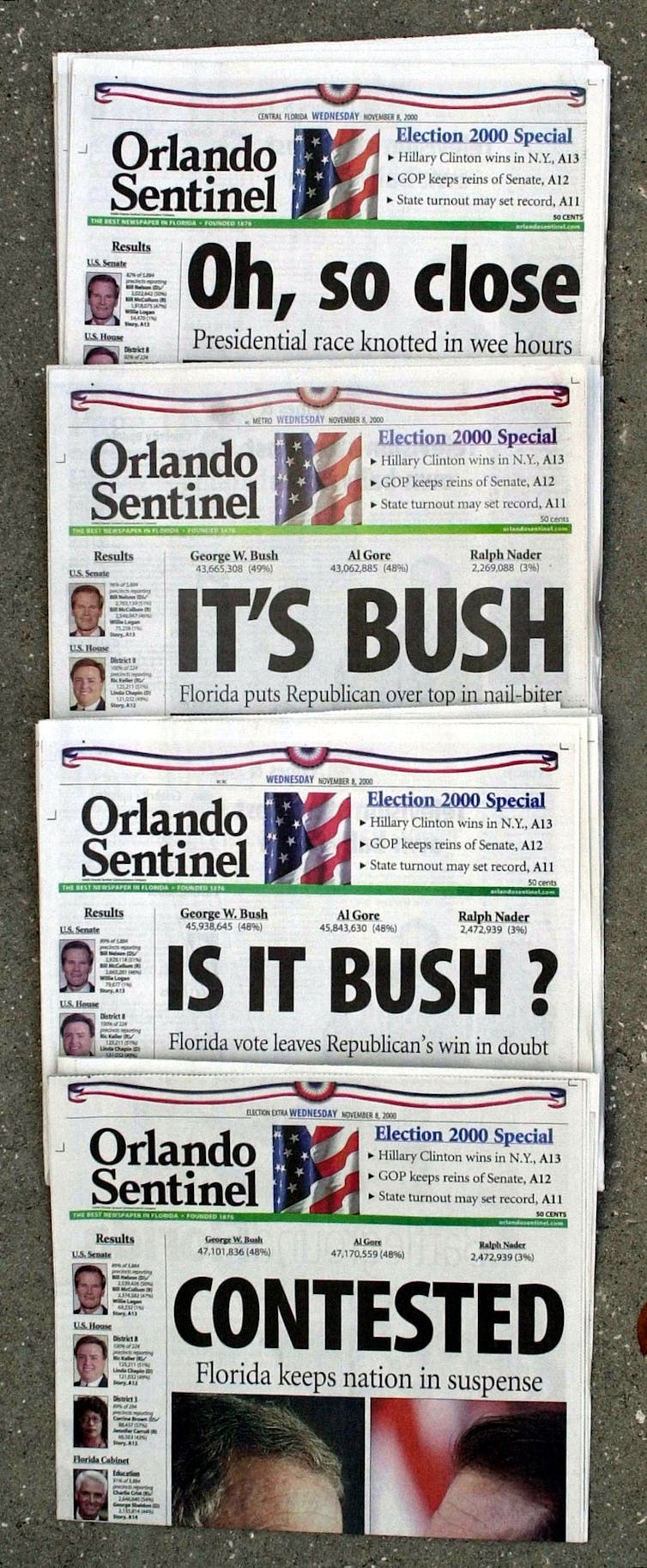

Bush v. Gore was the culmination of numerous lawsuits triggered by the close vote in Florida. After both campaigns filed lawsuits in various state courts, the Florida Supreme Court decided to extend the hand-counting of votes until Nov. 26, 2000, eight days after the state’s statutory deadline for certifying the election results to Congress. The Bush campaign challenged that decision in the U.S. Supreme Court.

In a 5-4 opinion, the Supreme Court ruled that the mandated recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court violated the equal protection clause.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the failure of Florida courts to establish a uniform standard for determining legal from illegal votes in a recount created the possibility of different standards being used by different counties. The court concluded that this was a violation of 14th Amendment rights to due process and equal protection of the law.

‘The people’s will’

Although the facts of Bush v. Gore were unique and messy, as the court itself noted, it is not difficult to foresee one or even several similar challenges arising in the 2020 election. And where the lawsuits involved in Bush v. Gore all originated in Florida, this time the chaos may reach across several states.

Indeed, many experts foresee the possibility of lawsuits in several key states this November. Depending upon the nature of the claim made by the party bringing the lawsuit, many – if not most – of these cases will originate in state courts, and at pretty much the same time.

But it is also quite likely, as happened in the 2000 election, that some – though not all – of the decisions in these cases will be appealed to the Supreme Court because one party could claim the decision violated the Constitution.

This sets up a situation where the outcome of the election may turn on several court decisions, some of them involving state courts.

And that could lead to a political problem.

In the 2000 election, the Supreme Court’s decision effectively settled the election, but only because both parties and the people chose to accept the decision – or more precisely, chose to accept the court’s authority to make the decision.

Whether the public would accept an electoral result determined by a state supreme court, or some combination of state court and federal court decisions, seems much more doubtful. Moreover, in some states, supreme court judges are elected. A subset of those are partisan elections, where judicial candidates run under a party affiliation, raising the prospect that some of these decisions will appear to be politically motivated.

Indeed, 20 years after Bush v. Gore, in an era of hyperpartisanship, it does not seem obvious that the public would – or even should – accept the Supreme Court’s legitimacy as a neutral adjudicator.

The recent death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg highlights a simple fact: The Supreme Court is itself a critical issue of intense partisan conflict in the 2020 election.

If Ginsburg’s seat is not filled before the election – and, as a constitutional scholar, I believe there are compelling reasons it should not be – then an eight-justice court could split 4-4 in the imaginary case of Biden v. Trump. Such a decision could look to citizens like party politics dressed in black robes rather than an exercise in constitutional reason.

Bush v. Gore triggered a national debate not only about what the Constitution means, but also about the health and well-being of the American polity. As I have written elsewhere, “Political democracies do not choose their leaders by judicial fiat. They elect them, usually by political majorities.”

And as Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer notes, “the people’s will is what elections are about.”![]()

John E. Finn, Professor Emeritus of Government, Wesleyan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.