Veterinarians and animal health scientists keep domestic animals healthy and look for ways to combat and contain contagious diseases that can not only cause extensive damage to livestock and affect the food supply, but also can infect people (about sixty percent of human diseases come from animals). When working in full protective gear in biocontainment laboratories, biological ‘space suits’ and all, scientists may need to discuss important topics or perform demonstrations remotely in real time. They currently cannot do that without leaving the lab and changing into regular clothes, which involves a number of steps for decontamination, because suitable technology does not exist for such environments. Until now.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) addressed that problem with a project called Multi-laboratory International Collaborative Environment (MICE) that developed a videoconferencing and multimedia network to be used during laboratory work. Although video conferencing already exists, many labs cannot use it in real time mostly due to the special circumstances in biocontainment labs where scientists are required to wear biohazard protective gear, which keeps at bay virulent microorganisms.

That is why MICE has a range of capabilities for connecting scientists from such labs and the field (farms) to colleagues and public officials. These capabilities include sharing live test results, reports, video and images, important in supporting incident command decision-making.

“Taking advantage of connecting with other institutions that are doing similar research and have highly specialized subject matter experts in the United States and around the world will help us to develop better agricultural disease screening, diagnostic tools and therapeutics,” said Dr. Krista Versteeg, an ORISE fellow for S&T’s Chemical and Biological Defense Division. “It would also help in the case of an outbreak response when we need to communicate with laboratory personnel across an area to get information in real time, which in a sense can help coordinate the response.”

In early April, S&T launched five MICE pilots at state, federal and academic laboratories for animal diseases, where the network will have a test run for several months to generate user feedback needed for further improvements of the technology.

During the pilot exercises, MICE will link researchers and students for a range of scenarios such as remote training, discussions and demonstrations of necropsies, ongoing research, new techniques, unique disease cases (anthrax, tularemia or rabies); and will assist with disease outbreaks, public health response and more. These labs have different levels of containment, depending on how dangerous the disease agents are to humans. Researchers must wear a variety of gear—from just lab coats and gloves to full biological containment suits and respirators.

“The communication and data sharing between those labs is currently difficult for many reasons. This technology will help scientists work together,” said Dr. Versteeg. “Real-time connection is important for efficient problem solving.

For example, field agents of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection often come across agricultural products. As they inspect the products in a lab looking for pests, the agents may find something unfamiliar and could have a videoconference with a specialist from another lab to quickly resolve the issue.

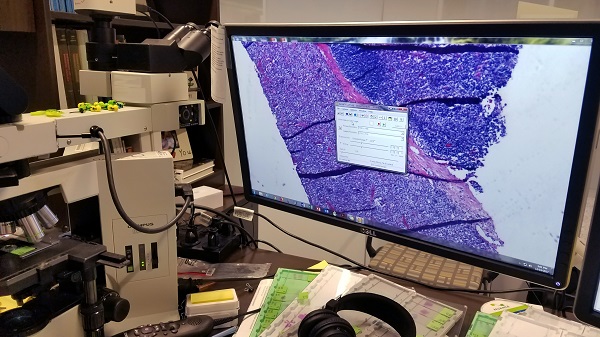

Monitors and cameras would not be the only equipment hooked to the MICE network. Scientists can also attach other instruments like computers and microscopes so that data and files are shared between labs during a videoconference.

“It has the plug-and-play capability, so you can bring your own devices, such as lab cameras or mobile field platforms like iPads, microphone headsets, microscopes, sequencing machines or other pathogen analyzing machines, and plug them into the network,” said Dr. Rosanna Robertson, an S&T Program Manager for MICE.

MICE was developed by the Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases, which is one of the Centers of Excellence. Laboratories can access the network from the Internet via Polycom Collaboration Server.

The MICE network was inspired by an Australian project for biocontainment labs that used videoconferencing and data sharing to connect scientists in Australia. S&T developed the next generation network to include new technologies, which will be available for both government and private institutions at home and eventually abroad

“Enabling participation from the international community is important because efficient response to disease outbreaks, both animal and human, requires global coordination and awareness,” said Dr. Robertson.

The MICE technology is customizable and expandable depending on the lab. Its cost depends on the equipment that would be attached and the software necessary to support the network. The biggest cost saving comes from something else.

“If a training can happen virtually, that is much more cost effective than sending a team of people,” said Dr. Robertson.

Since the beginning of this year, S&T has been presenting MICE at many international conferences with the goal to raise awareness, advertise the capability, and help interested groups join the network.

As the MICE project is nearing its completion, S&T is planning to transition the responsibility, operations and maintenance to S&T’s Plum Island Animal Disease Center and will be working to expand the network to include new members.