When two young Chinese nationals were abducted in broad daylight and brutally killed earlier in June in Pakistan, the Islamic State claimed responsibility.

The two 20-somethings were first reported to be language teachers working in Pakistan. But then The Global Times, a popular tabloid of the Chinese Communist Party’s mouthpiece, People’s Daily, offered this explanation for the murders: “They were involved in illegal preaching led by South Korean missionaries”.

In a tepid and bizarre response to the killings, China’s foreign ministry said that it was investigating the incident and it urged “all Chinese nationals travelling overseas to observe local laws and regulations [and] respect local customs and practices”. It has yet to confirm the deaths.

Blaming the victims

The story must have been disappointing for ISIS in Pakistan, too. The group carried out the terrorist attack and claimed full responsibility, only to find that South Korean missionaries were the ones taking the heat for exerting undue influence over young Chinese nationals in atheist China.

The only mention that the Islamic extremists got from Beijing was this standard rhetoric: “China firmly opposes all kinds of terrorism and extreme violence against civilians, and supports Pakistan’s efforts to combat terrorism and safeguard domestic security.”

The government has been characteristically tight-lipped on all fronts of this case, with no discussion or reports allowed on state-controlled media. Neither criticism nor awkward details have yet entered the mainstream, though on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, outrage over Beijing’s victim-blaming and attempts to change the subject quickly began percolating.

The Chinese public still does not even know the names of the dead; in the official narrative, they remain anonymous citizens who were abducted, their whereabouts unknown.

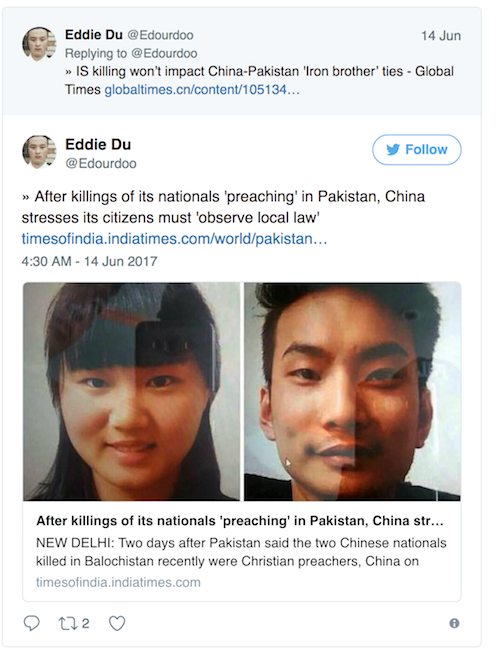

English-speaking readers are more in the know. On June 12, Reuters reported that the abducted Chinese nationals were 24-year-old Lee Zing Yang and 26-year-old Meng Li Si. These slightly errant facts were later corrected by the Hong Kong newspaper, Ming Pao, which confirmed the names of the dead as as Li Xinheng (李欣恒) and Meng Lisi (孟丽斯).

When Ming Pao’s reporters visited the family of Li Xinheng, Li’s parents said they were not allowed to speak to media.

When Ming Pao’s reporters visited the family of Li Xinheng, Li’s parents said they were not allowed to speak to media.

iFeng.com, a popular online news portal owned by Hong Kong-based Phoenix TV, was the first in China to release photos of the two victims and circulate, on June 9, ISIS’ claims of responsibility.

This video is no longer available on iFeng. Days after its posting, and perhaps unrelated to it (but likely not), China’s press watchdog ordered the website to shut down its streaming service, saying it carries “many politically-related programs that do not conform with state rules and social commentary programs that propagate negative remarks and opinions”.

Unstoppable CPEC

Pakistan, known as China’s “all-weather friend”, has echoed Beijing in identifying the victims as illegal preachers, and defended itself by saying it “offered security to the pairs but was rejected”.

China, in turn, praised Pakistan for its “all-out efforts” to ensure the security of Chinese nationals and institutions in Pakistan, and pledged the friendship and that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) would not be undermined.

The CPEC is a flagship initiative for China’s ambitious economic and geopolitical blueprint One Belt One Road, widely regarded as a game changer for Asia and beyond.

The US$54 billion CPEC, which includes massive infrastructure projects in transportation, energy, and trade, would be the biggest independent foreign investment Pakistan has ever received.

The initiative aims to link China’s restive Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang with the strategic Pakistani port of Gwadar, passing through the controversial Kashmir area, which both Pakistan and India claim.

Javedpk05/Wikimedia, CC BY

Since it kicked off in 2015, Chinese nationals have been swarming into Pakistan, with around 15,000 Chinese directly working on the projects and many others eyeing related business opportunities.

In theory, this makes the safety of Chinese nationals living and working overseas a real concern for Beijing.

Zhao Gancheng, a Chinese expert on Asia-Pacific studies, noted that as China’s global presence and influence is growing, extremists may target Chinese nationals “for ransom or for sensational media impact”.

‘Going global comes with risks’

China’s clear desire was to leave its ambitious project with Pakistan unscathed by this international incident. But the economical and geopolitical bet taken by China with Pakistan is a risky one.

The World Economic Forum ranks extremism-plagued Pakistan as the world’s fourth least safe country in the world, and this isn’t the first case of Chinese being abducted or attacked.

Beyond the terrorist threat presented by the Taliban, ISIS and other separatist insurgencies, the CPEC project has faced fierce opposition within Pakistan. Many commentators have expressed concern that the economic corridor is heavily skewed in China’s favour.

Beijing is particularly unrest-averse right now. It doesn’t want to be drawn into direct engagement with overseas counter-terror efforts, nor does it want any social upheaval at home in the lead-up to the 19th National Congress in September 2017, when the Communist Party will pick its new leader.

From this perspective, the victim-blaming, media censorship, together with the comment from China’s Foreign Ministry are less surprising . “Going global comes with risks,” was the explanation its spokeswoman Hua Chunying gave when asked about the link between the murder and CPEC.

![]() This response suggests that the slain Chinese is the price China has to pay to achieve its grand vision of rejiggering the world order. Should it be?

This response suggests that the slain Chinese is the price China has to pay to achieve its grand vision of rejiggering the world order. Should it be?

Yuan Zeng, PhD candidate in journalism studies, City University of Hong Kong

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.