President Donald Trump recently announced his plan to dispatch National Guard troops to the southern border to assist with security efforts.

The Army National Guard is the oldest defense force in the nation, formed in 1636 as three militia regiments in the Massachusetts Bay Colony armed to defend against the Pequot Indians.

The actual term “National Guard” was first used in 1824 for New York state militia units who wished to honor the Marquis de Lafayette and his French National Guard. The title was officially adopted in 1903 and describes the force which, unusually, falls under both federal and state control.

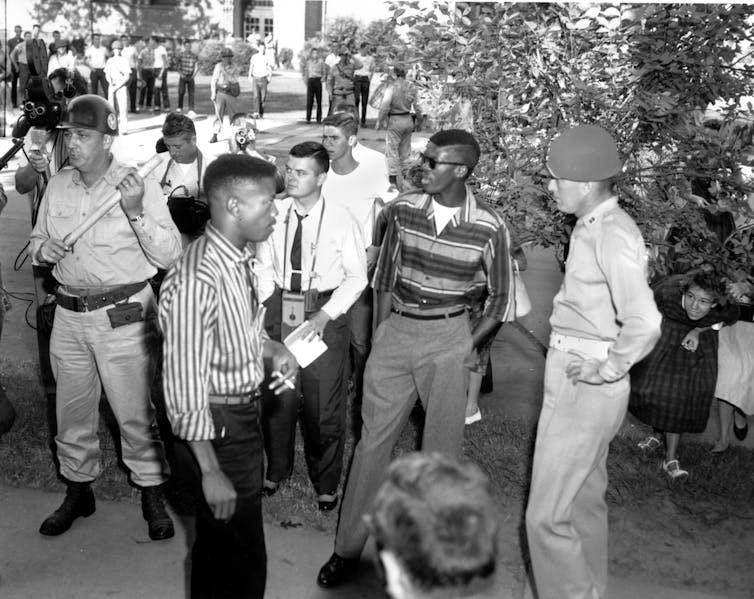

The National Guard – both Army and Air – is the only military force that is shared by the states and the federal government, and both the president and state governors can order their deployment. As “commander in chief” of their states, governors may send their state National Guard to respond to natural disasters – floods, fires or earthquakes – but also emergencies such as the 1999 rioting during the Seattle World Trade Organization meeting.

The U.S. Constitution’s “militia clause” authorizes the use of the National Guard by the federal government to “execute the laws of the Union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions.” It was this authority that allowed governors to answer President George W. Bush’s call for Guard assistance in airports immediately after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

There are national guards in every state plus Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, Guam and the Virgin Islands. Each of the 54 organizations is headed by an adjutant general, who reports to the chief of the National Guard Bureau, a four-star general, who has been a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff since 2012.

The majority of the Guard’s 435,000 members have civilian jobs elsewhere. Their duties are augmented by an Active Guard and Reserve – a full-time National Guardsman who keeps the Guard and Reserve running full time.

But there are limits – laid out in the aftermath of Civil War – that restrict the use of federal military personnel domestically. The Posse Comitatus Act was signed in 1878; it effectively removed federal troops from occupying the South.

Grumbling has already begun that Trump’s plan to deploy the Guard to the border violates the Posse Comitatus Act, since the act restricts federal military support of domestic law enforcement. Yet earlier presidents, including both Barack Obama and both Presidents Bush, sent the Guard to the U.S.-Mexico border to help with security.

![]() There’s a significant exception in the legal framework that covers the Guard that can be used in this situation: At the suggestion of the president, governors could deploy their Guardsmen to the border as long as they remained under state, not federal, jurisdiction. The legal debates have just begun.

There’s a significant exception in the legal framework that covers the Guard that can be used in this situation: At the suggestion of the president, governors could deploy their Guardsmen to the border as long as they remained under state, not federal, jurisdiction. The legal debates have just begun.

Frances Tilney Burke, PhD student, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.