Using the profile pictures of over one million participants, researchers at Stanford show that a widespread facial recognition algorithm can expose people’s political orientation with stunning accuracy. Political orientation was correctly classified in 72% of liberal–conservative face pairs, remarkably better than chance (50%). Accuracy was similar across countries (the U.S., Canada, and the UK) and online platforms (Facebook and a dating website).

The researchers note that they have not created a privacy-invading tool. “Very much like in the context of our previous work on sexual orientation and Facebook Likes,” they are instead warning against existing technologies that have been used for years by companies and governments. “Do not shoot the messenger. ”

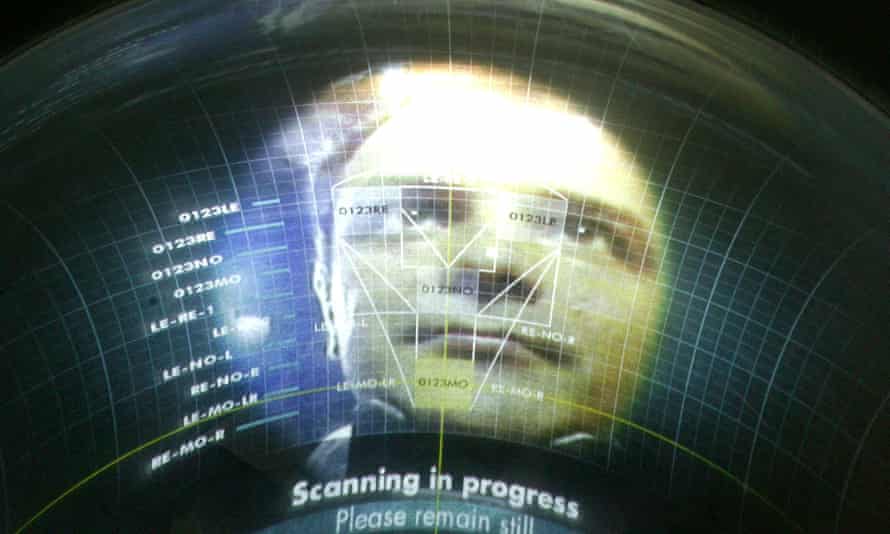

Widespread use of facial recognition technology poses dramatic risks to privacy and civil liberties. Ubiquitous CCTV cameras and giant databases of facial images, ranging from public social network profiles to national ID card registers, make it alarmingly easy to identify individuals, as well as track their location and social interactions.

Pervasive surveillance is not the only risk brought about by facial recognition. Apart from identifying individuals, facial recognition algorithms can identify their traits. Like humans, facial recognition algorithms can accurately infer gender, age, ethnicity, or emotions. Unfortunately, the list of personal attributes that can be inferred from the face extends well beyond those few obvious examples. Past work has shown that widely used facial recognition technologies can expose people’s sexual orientation and personality. This work shows that it can also expose political orientation.

While many other digital footprints are revealing of political orientation and other intimate traits, facial recognition can be used without subjects’ consent or knowledge. Facial images can be easily (and covertly) taken by law enforcement or obtained from digital or traditional archives, including social networks, dating platforms, photo-sharing websites, and government databases. They are often easily accessible; Facebook and LinkedIn profile pictures, for instance, can be accessed by anyone without a person’s consent or knowledge. Thus, the privacy threats posed by facial recognition technology are, in many ways, unprecedented.

Some may doubt whether the accuracies reported here are high enough to cause concern. Yet, our estimates unlikely constitute an upper limit of what is possible. Progress in computer vision and AI is unlikely to slow down anytime soon. Moreover, even modestly accurate predictions can have tremendous impact when applied to large populations in high-stakes contexts, such as elections. For example, even a crude estimate of an audience’s psychological traits can drastically boost the efficiency of propaganda and mass persuasion. “We hope that scholars, policymakers, engineers, and citizens will take notice,” the researchers declare.