A new study in GSA Bulletin seeks to constrain how often and where faults cause earthquakes under the heart of Seattle.

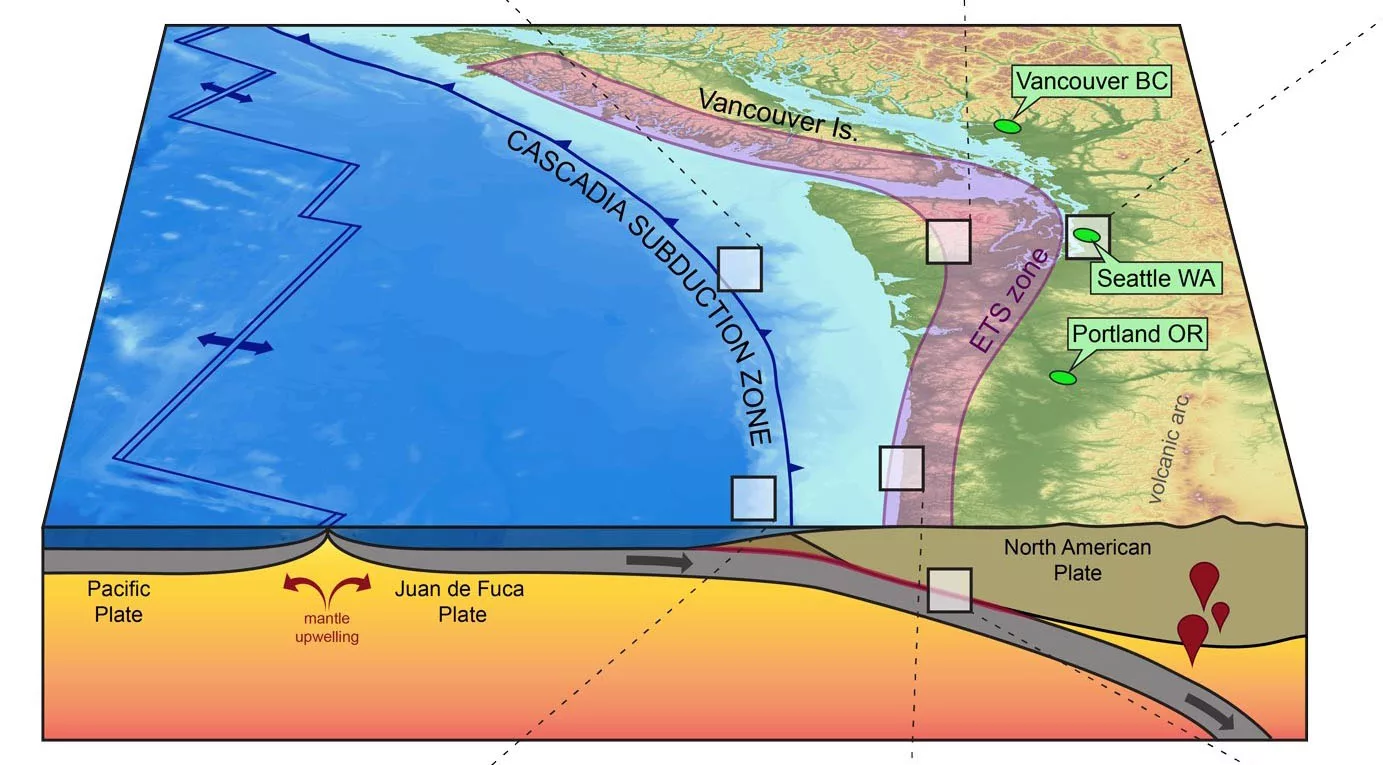

In the Pacific Northwest, big faults like the Cascadian subduction zone located offshore, get a lot of attention. But big faults aren’t the only ones that pose significant hazards, and a new study in the journal GSA Bulletin investigates the dynamics of a complex fault zone that runs right under the heart of Seattle.

“My job as a paleoseismologist,” says Dr. Stephen Angster, a research geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Earthquake Science Center in Seattle and lead author of the new study, “is to figure out when and how often these local faults rupture, which would help us predict roughly when we come in the window of the next potential rupture.”

The study focuses on the east-west trending Seattle Fault Zone, or SFZ, which cuts through Bainbridge Island and Seattle. Geologists have known for a while that the main fault appears to rupture on time-scales greater than 5,000 years, though it’s only in recent years that geologists have begun to map out smaller secondary faults within the SFZ. However, the tools geologists use to calculate earthquake hazards don’t commonly include these smaller, secondary faults, and Angster hopes that learning more about them could help understand their hazard potential.

“When we generate the National Seismic Hazard Model for the U.S., we leave out these shorter faults because they don’t meet the minimum requirement for length and thus are considered to have a low magnitude potential,” says Angster. “In the case of the SFZ, we don’t fully understand the rupture dynamics at depth, but they’re rupturing more frequently and pretty close to home.”

The SFZ helps accommodate strain, or deformation, that’s the result of squeezing of the Earth’s crust from Portland, Oregon, to Vancouver, British Columbia. Strain accumulates constantly, but is released only periodically through earthquakes. Of the total strain in the region, the SFZ takes up about 15%. Additionally, the fact that geologists can’t directly see the faults on Earth’s surface, makes it harder to study their dynamics.

Instead, Angster and his colleagues use techniques that give clues into the subsurface, like surveys that measure small magnetic variations of the underlying bedrock. They can also look for evidence of past surface-rupturing earthquakes by closely examining high-resolution lidar images, which allow them to see through the thick tree canopy and find scarps that formed when the ground was displaced during a past rupture. Then, they dig trenches across the scarps to figure out how long ago the ruptures occurred and how big they were.

The team then documented the histories of two newly discovered secondary faults in the SFZ and found that secondary faults are rupturing there about every 350 years—far more often than the main fault.

“The surface ruptures from earthquakes within the SFZ have been dominated within the last 2500 years by these secondary fault events,” says Angster.

The most recent rupture appears to have been in the nineteenth century, according to radiocarbon and tree-ring dating of trees that diedafter an earthquake. Going forward, Angster and his colleagues hope to refine their understanding of these secondary faults and determine how much hazard they pose to the four million residents of the Seattle area.

“The thing about the Seattle fault is that in the Cascadia event, we’ll shake pretty hard and long when it happens,” says Angster, “but it’s likely not going to be as destructive for Seattle as a major event on the Seattle fault. I think we’re still trying to wrap our heads around the size and the potential of these smaller faults and the relationship between main fault rupture and these more frequent, smaller ruptures.”

– Rudy Molinek, GSA Science Communication Fellow