The rise of social media and fake news challenge long-held assumptions about the First Amendment and are undermining the functioning of the “the marketplace of ideas,” a Duke professor argues in a new article.

“There are a number of very specific ways in which the structure and operation of today’s digital media ecosystem favors falsity over truth; and this shifting balance raises some troubling implications for how we think about the First Amendment,” says author Philip Napoli, professor at Duke’s Sanford School of Public Policy.

Much of our thinking about the First Amendment assumes that the answer to false speech is more speech, or counter-speech, and that the truth will triumph in the marketplace of ideas, he says.

Yet changes in the news media – such as consumption via social media, the speed and targeting capabilities of fake news purveyors and “filter bubbles,” where people only see news that reinforces their views — mean we can no longer assume legitimate news will win, Napoli says.

The article, “What If More Speech Is No Longer the Solution? First Amendment Theory Meets Fake News and the Filter Bubble,” was published Monday in the Federal Communications Law Journal.

In the last two decades, technological and economic changes have undermined legitimate news production and enhanced fake news. Despite the flood of news available online, the actual proportion of original reporting is declining.

“Original reporting is costly. Fake news is cheap,” says Napoli.

Meanwhile, audiences have increasing difficulty distinguishing between true and false news. Recent surveys suggest people now evaluate news not based on its source, but based on the trustworthiness of the person who shared it.

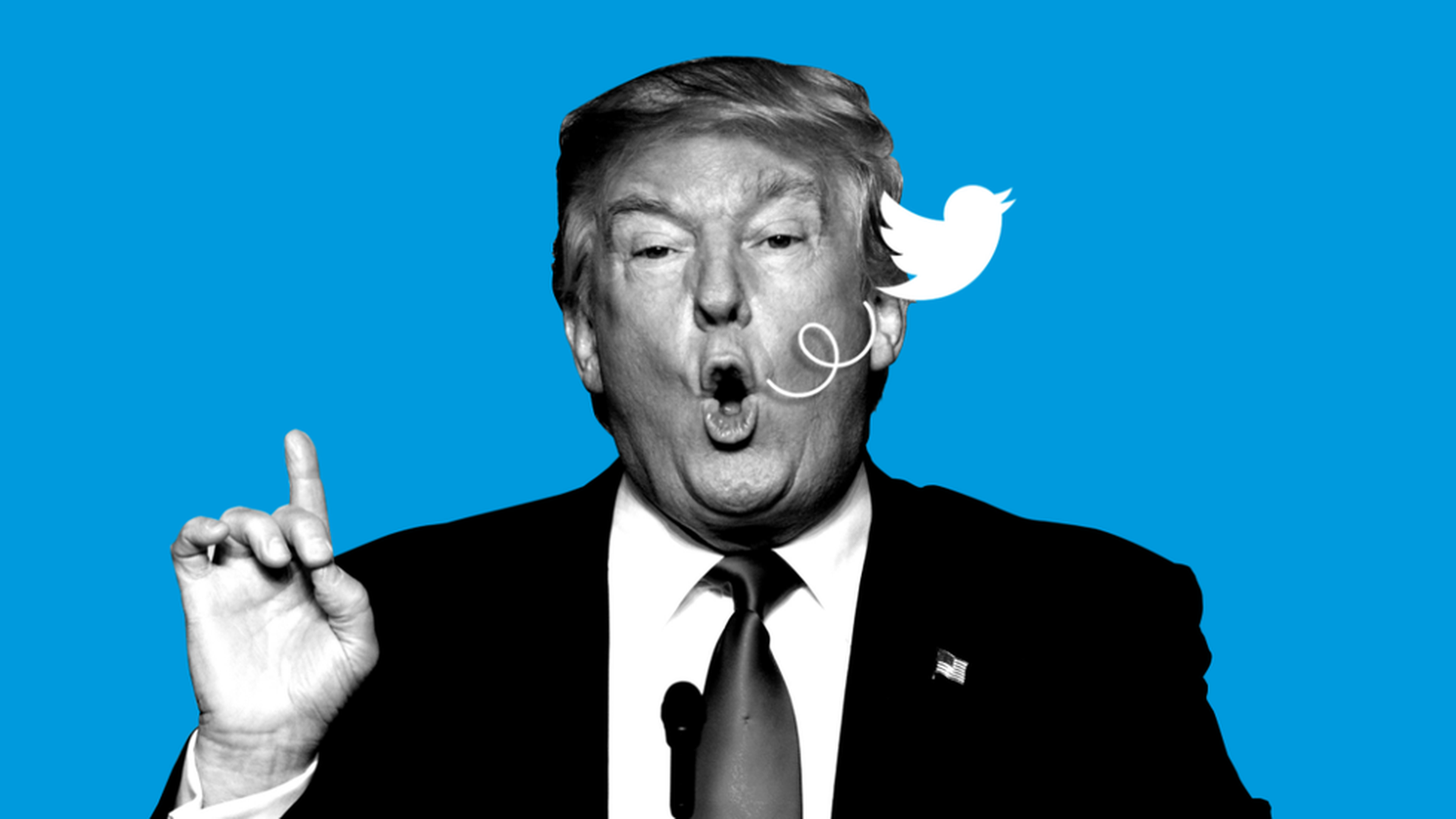

The 2016 election is a case study of the failure of the marketplace of ideas, Napoli said. Filter bubbles and fake news, including Russia’s online propaganda efforts, made it difficult for citizens to access accurate information, Napoli said.

Meanwhile, big social media platforms have considered themselves tech companies, not publishing or media companies. The public service ethos and journalistic standards of traditional media are not part of their business models. Google and Facebook have not acted as gatekeepers keeping out fake news in same way that traditional news outlets such as The New York Times or ABC News do.

Social media companies also bear no legal liability for falsehoods, Napoli notes.

He recommends that social media companies develop a robust public service ethos appropriate to their responsibilities as providers of the news and information essential to a functioning democracy.

The recent Congressional testimony of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg shows that Congress has taken an interest in the issue.

“The key question is if or how government intervention might be an appropriate response. Germany recently adopted a law that requires social media platforms to remove stories identified as fake news or face government-imposed fines,” Napoli says.

In the U.S., broadcast media adhere to federal regulations about false news reporting, and the Federal Communications Commission can choose to investigate reports of intentional falsification of the news.

“It is important to recognize that concerns about fake news have an established foothold in the U.S. media regulatory framework,” Napoli says.

Napoli addresses these issues in his forthcoming book, “Social Media and the Public Interest: The Rise of Algorithmic News and the Future of the Marketplace of Ideas.” His research is supported by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York.